Hallucinations For Accelerated Mutants — A Mondo 2000 Retrospective

This article was originally written for and published at Neon Dystopia on August 28th, 2017. It has been posted here for safe keeping.

It’s difficult to explain Mondo 2000 to someone who hasn’t experienced it before. That’s really what I would call it at the end of the day: an experience. Like a hallucinogenic trip, or a roller coaster ride, or that tingle that you get after a first kiss — it’s something you just don’t really get by having it described to you.

I first became aware of Mondo 2000, the glossy cyberculture magazine which ran from 1989 to 1998, in the much more recent year of 2012. Late to the party, I admit, but sometimes you just can’t get there on time. In 2012, I began to research hacking magazines as I was getting worried that some of them would soon disappear from the world without a trace. Somewhere out there sat old, possibly moldy magazines full of articles and stories that once appealed to the hacking subculture. Nobody was saving them, so I decided to start. I began patrolling. Amazon, eBay, and basic HTML sites that haven’t been updated since the early days of the web became my usual haunts. Between monitoring auctions and mailing old email addresses, I was able to begin buying these publications. The ones I could find, I would wrap in archival-grade plastic and scan into my computer when I had the time; a slight pit stop before pushing them to the Internet Archive. Now, five years later, I agonize over the magazines that I haven’t even heard of yet. I learned a lot about the technological landscape of the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, but I didn’t have anything really resonate with my until I came across Mondo 2000. Sitting right on the border between the then-bleeding-edge and the surrealistic not-so-distant future, Mondo fostered a generation of tuned-in misfits who were making their way through hyperculture. This could have been me in a different time, but all I can do now is read the back-issues while wearing a bootleg Mondo t-shirt. Looking back, it feels like some sort of technophilic fever dream for kids with psychedelics and a ‘net connection. Drugs, sex, and the digital revolution dripped from the warm, colorful pages. Would you want to wake up?

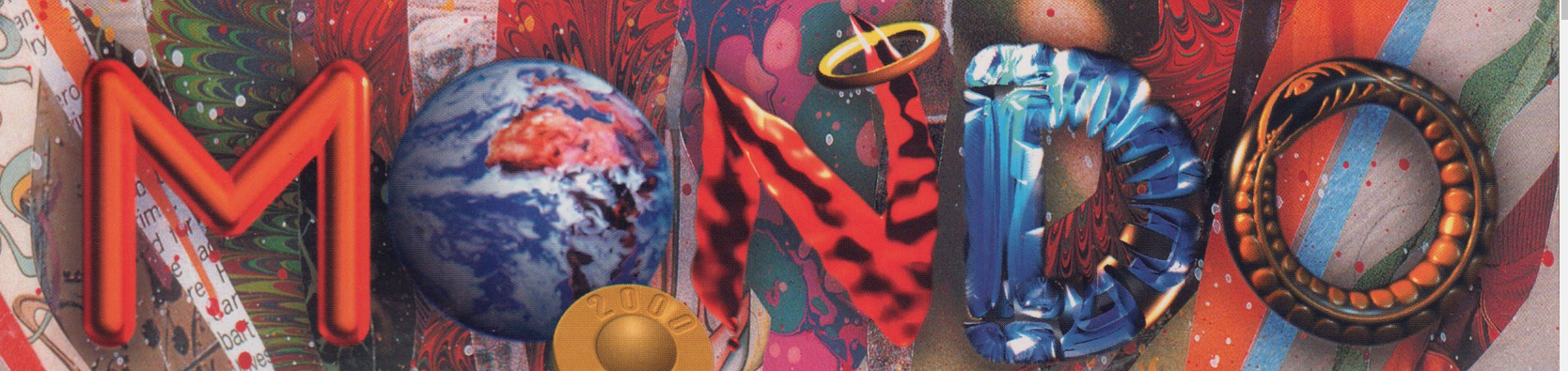

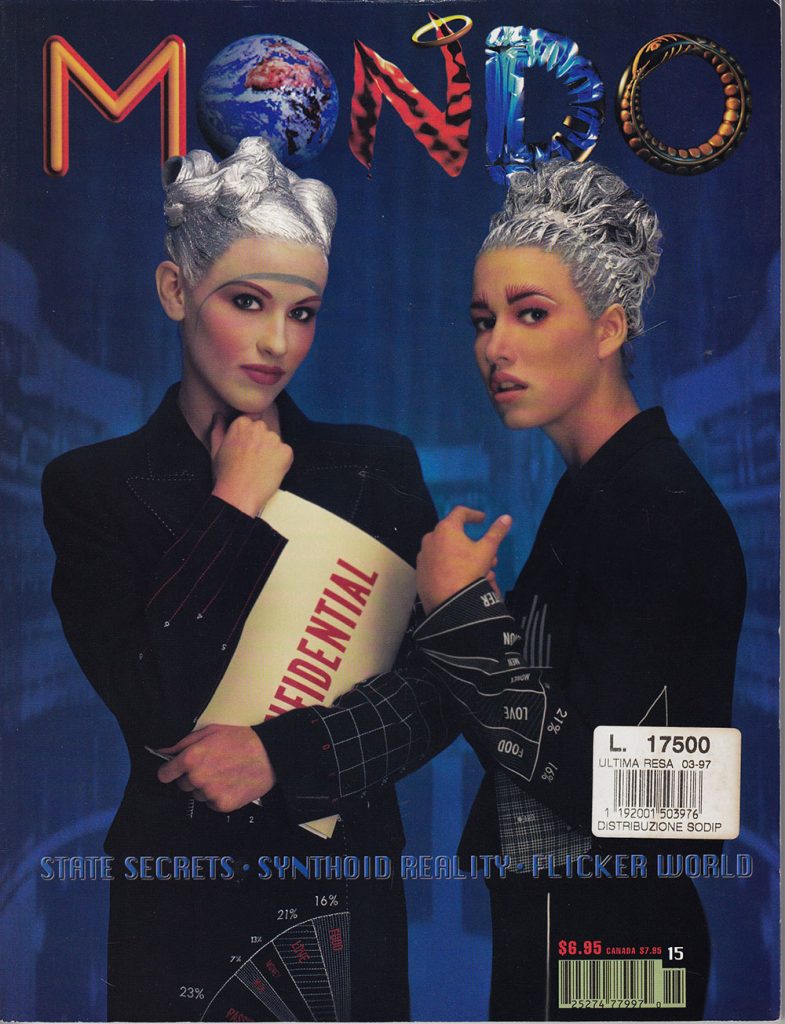

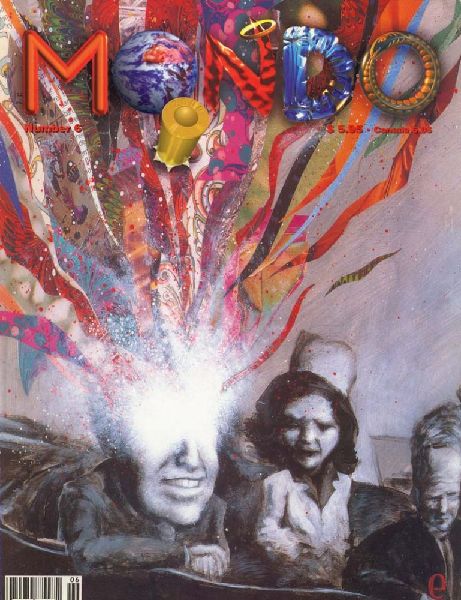

Mondo 2000 issue 15 cover.

For many, Mondo 2000 was seen as just the thing a sharp-tongued, budding cyberculture needed. Others saw it as pseudo-intellectual nonsense, fabricated garbage that didn’t really mean anything. To the Mondoids, the dedicated followers, it didn’t matter if the normies didn’t understand. Mondo 2000 was playful, eccentric, irreverent, and brash — it worked on its own terms and it worked well. Yet, Mondo 2000 did always have a built-in expiration date. With a name like that, it could never go on forever. After 14 issues, Mondo ceased publication. The print was dead, but the ideas would live on — the infection would keep spreading. While Mondo hit the scene at an interesting time in the advancement of technology, it has a much more ludicrous origin story. Author Jack Boulware once reported in a famous 1995 postmortem, “Mondo’s history reads as if fabricated on another planet, spewed forth by a sweaty cyberpunk novelist tripping on nasal-ingested DMT.”

He isn’t wrong.

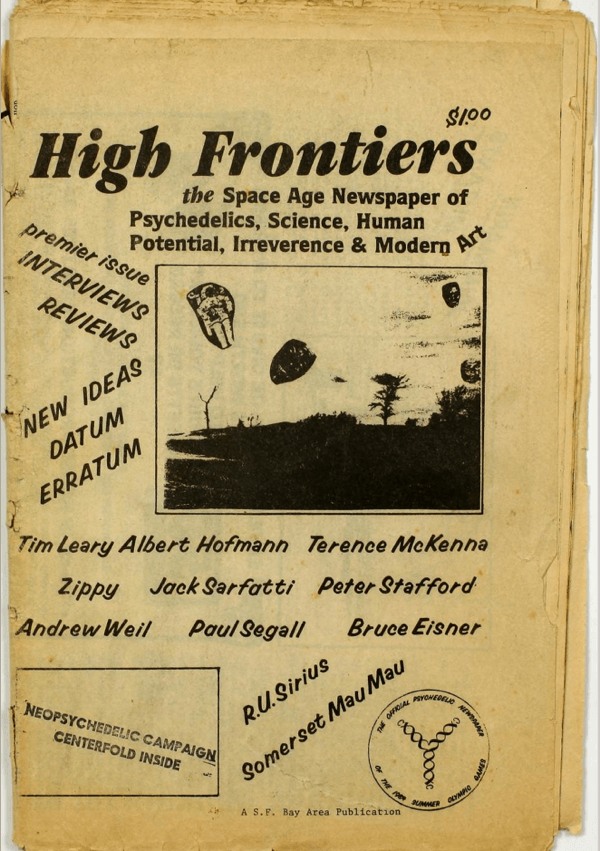

The Edge Of A High Frontier

Mondo 2000 didn’t just pop up one morning out of nowhere. The roots of Mondo go all the way back to 1984. Ken Goffman published the first issue of High Frontiers, your source for “Psychedelics, Science, Human Potential, Irreverence & Modern Art,” in a small run of 1,500 copies. The first issue embraced mind expansion with interviews featuring Terrence Mckenna, Bruce Eisner, Timothy Leary, and even Albert Hoffman, the father of LSD. Goffman, an ex-yippie, former New York musician who had since moved to California, had already adopted his dadaist R . U. Sirius persona when he decided to embark on a publication that combined psychedelic exploration, science, and high technology. The premier issue, published in a newspaper format, featured his moniker on the cover alongside co-conspirator “Somerset MauMau.” The innards were packed with walls of text and tongue-in-cheek photographs that looked like cut-outs from Life magazine. The next issue would need to keep up the energy, and the fun.

R. U. Sirius.

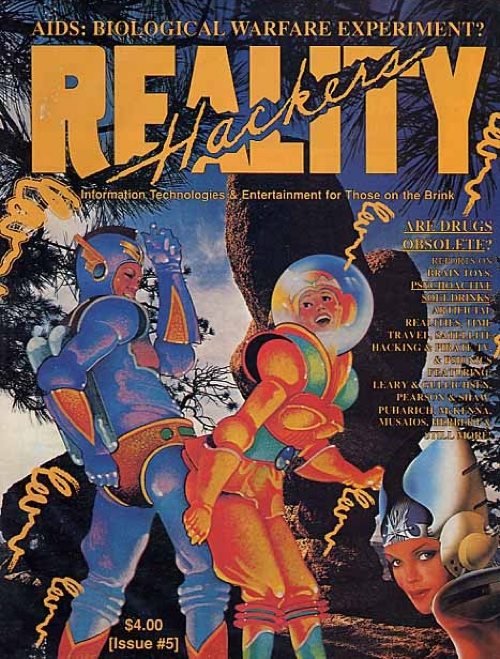

Sirius’ life would change one night as he was distributing the first issue of High Frontiers at a birthday party: he would meet Alison Kennedy. Kennedy, the wife of a UC Berkeley professor and daughter of a wealthy California family, captivated Goffman. Soon, Kennedy would come to join the band of “Marin Mutants” (named for High Frontier’s Marin, California headquarters) that worked on the publication, sporting names like “Lord Nose” or “Amalgum X.” Meeting in a local pizza parlor with oddly-abysmal foot traffic, the High Frontiers staff would plot out their next articles. The second issue of High Frontiers, published a year after the first, would go on to include interviews with physicists, research on hallucinogens, and reviews of art and literature. By issue three, science and technology had become more of a main focus with articles on memory enhancement, psychoactive software, and quantum physics. Of course, drugs were still held in high regard with articles like “MDMA: Safe As Ice Cream,” and Kennedy’s own gonzo-anthropological “Tarantella And The Modern Day Rock Musician,” about hallucinogenic tarantula venom. Kennedy would soon go on to adopt a new persona of her own: Queen Mu, Domineditrix. After issue four of High Frontiers, Sirius and Mu would change the name of the magazine to Reality Hackers, which better represented the mix of articles on mind-expanding drugs and computer-based technology. As the magazine mutated, so did the staff. New additions included anarchist hacker Jude Milhon (who would become known as St. Jude) and the in-your-face Michael Synergy (real name unknown), a cyberpunk keen on toppling all of the powers that be.

High Frontiers issue 1. Read through all of the issues here!

With operations now moved to a large wooden house in the Berkeley Hills, Reality Hackers became a lightning rod for new, more diverse happenings of the psycho-technical fringe. There were articles on smart drugs, virtual reality, chaos theory, and isolation tanks, some featuring leading experts in these new and/or obscure fields.

Distributors, however, had no idea what to do with Reality Hackers and thought it was a magazine about literally hacking people to bits. Sirius would eventually be approached by Kevin Kelly of Whole Earth Review, the magazine spawning from Stewart Brand’s seminal Whole Earth Catalog, to work on a new digital culture magazine called Signal. Sirius ultimately declined in order to pursue a new mutation of Reality Hackers, honing-in on the young cyberpunk movement. Sirius and Mu would soon change the name of the magazine again to Mondo 2000 after publishing only two issues under the Reality Hackers name.

Reality Hackers. Issue numbering takes place where High Frontiers leaves off. Read all of the issues here!

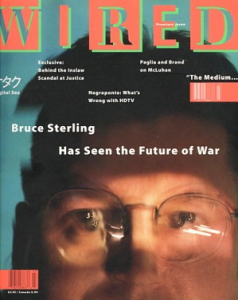

At first, Mondo 2000 still resembled Reality Hackers between the cover art and black-and-white interior. After Bart Nagel was brought on as Mondo’s art director, things took a turn as he completely reworked the design of the magazine. Featuring colorful layouts, expert photography, full-page illustrations, and surreal covers, the new magazine was as stylish and beautiful as it was informative. New content went hand-in-hand with the new design; there were articles on cyberspace, computer viruses, and conspiracy theories. Authors that would grace the first issue include Bruce Sterling, William Gibson, and John Shirley, each notable for their work in the cyberpunk sub-genre. Gibson, an ex-hippie who had published the ground-breaking Neuromancer in 1984 (the same year the first issue of High Frontiers premiered), particularly resonated with the Mondo style. While Gibson would write about fictional high-tech outsiders who took smart drugs and jacked into cyberspace, the Mondoids were living it.

Mondo 2000 issue 6, featuring cover art by Bart Nagel. Read a selection of Mondo 2000 issues here!

Mondo 2000 embodied the cyberpunk subculture, and often served as the premier source for trends and news within the space. It wasn’t long before the rest of the world was trying to catch up. Sirius was starting to get quoted by mainstream sources like the Boston Globe or the Chicago Tribune who were dipping a toe into the bizarre cyberpunk waters for the first time. If John Shirley is known as being the “godfather of cyberpunk,” Sirius may have entered public eye as the crazy uncle. The Mondo 2000 house was regularly a who’s who of the eclectic Bay Area characters. Aside from Sirius, Queen Mu, St. Jude, and Synergy, regulars included contributors like subscriber-turned-music-editor Jas. Morgan, psychotropic-explorer Morgan Russell, and the drug-loving bankers Gracie and Zarkov.

Much of the content development for new Mondo articles stemmed from outrageous parties thrown at the Mondo house. It wasn’t uncommon for different rooms to be filled with active interviews, parlour games, or conversation between unlikely guests. A virtual reality expert might discuss politics with a smart drug theorist. Timothy Leary could discuss virtual sex with a computer hacker. Someone might suddenly get up to dance or go to the kitchen to try a 2CB analogue mixed with piracetem. As Mondo helped those on the fringe meet the like-minded, the culture only grew and evolved with each new issue. More and more reporters from publications like Newsweek or The New York Times were flocking to Mondo for a controversial opinion or unconventional view of the future. Before long, zine writers and editors like Gareth Branwyn and Mark Frauenfelder of bOING bOING, and Jon Lebkowsky and Paco Nathan of FringeWare Review started contributing to Mondo. Authors like Rudy Rucker, Robert Anton Wilson, and Douglas Rushkoff began submitting work as well. While the Mondo 2000 parties could only exist locally, articles came in from every corner of cyberspace or alternative plane of existence. Mondo had become a hub of interaction for those beneath the underground.

A Little ReWiring

As Mondo 2000 hit its stride, a new publication was just starting to take shape. Years earlier in 1987, Electric Word (originally launched as Language Technology) became a prominent linguistic technology and computer culture magazine in Amsterdam. White it generally focused on linguistic technology, and computer culture, Electric Word featured such pioneers as Xerox PARC’s Alan Kay, AI expert Marvin Minsky, MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte, and even Mondo-regular Timothy Leary. After three years the magazine shuttered, leaving editor Louis Rossetto and ad sales director Jane Metcalfe without jobs. Partners in business as well as life, the pair decided to return to the United States and embark on a new magazine about cyberculture and technology. They wanted to call the publication “Millennium” to highlight the new technical revolution, but the name was already taken by a film magazine. John Plunkett, then the creative director, wanted to name it “Digit” (a play on “dig it” and “digital”).Eventually, they settled on Wired and started developing a prototype with a mission to decipher the new digital revolution.

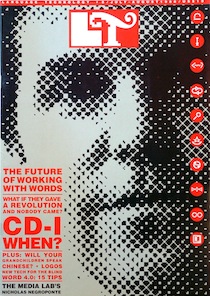

Cover for Language Technology issue 3. Read select issues here!

When Rossetto and Metcalfe arrived in California after shopping the publication around New York, they were soon introduced to the Mondo 2000 team. Things appeared to be friendly enough, and Queen Mu would often visit Wired’s offices and engage Rossetto and Metcalfe in conversation while handing out fresh issues of Mondo. Just starting out, the Wired team did its best to differentiate itself from the madcap, already-successful Mondo 2000. Both the Wired and Mondo groups were well aware of what one another was up to, and there was care taken to not step on any toes. The Wired team didn’t want to compete or be compared, they wanted to come into their own.

Louis Rossetto and Jane Metcalfe, via wired.com.

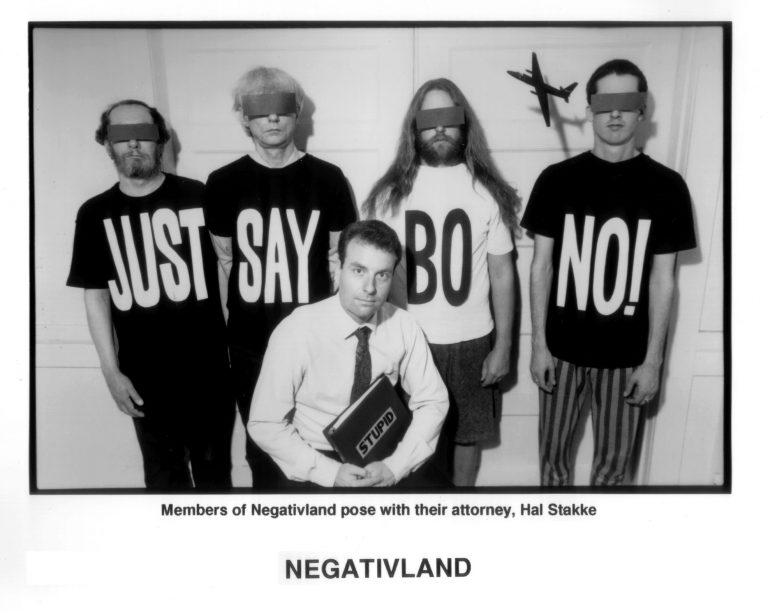

Not all was well within Mondo 2000 at the time. As Mondo grew, celebrities were vying to get into the magazine in an attempt to appeal to a more underground audience. When The Edge, guitarist for rock band U2, wanted to be examined for an article, Sirius recruited his friends from the band Negativland to conduct the interview. Negativland, who U2’s management had recently sued for copyright infringement, was a logical choice for Sirius. During the interview, The Edge didn’t know who he was speaking with and mentioned his views on intellectual property. At that point, Sirius revealed the band and trapped The Edge in his own hypocrisy. This resulted in one of the most well-known Mondo 2000 articles, but at the time it was strongly opposed by editor Queen Mu. After she refused the piece, Sirius had reached a tipping point and left Mondo, stepping down from his position as editor-in-chief. While Queen Mu eventually relented and published the article, Sirius never returned to his previous position. While he did eventually come back as a contributor, he also divested his share of ownership in the magazine.

Photograph of the band Negativland.

Too Weird to Live, Too Rare to Die

Though Mondo 2000 may have still been holding on to its popularity, there were increasing struggles to draw in advertisers. Mondo’s strong drug-friendly stance didn’t mix well with button-up businesses that had money to spend on product promotion, and the magazine suffered because of it. There was less cash on the table when writers looked to Mondo as a potential place to submit their articles, and many opted to go with other publications. While some continued to contribute to Mondo out of passion, outfits like the new Wired could afford to pay more per word. Looking back, Mondo was never truly run as a business looking to make as much profit as it could. Instead, it resembled an art project assembled by a hodgepodge of culture jammers and social engineers.

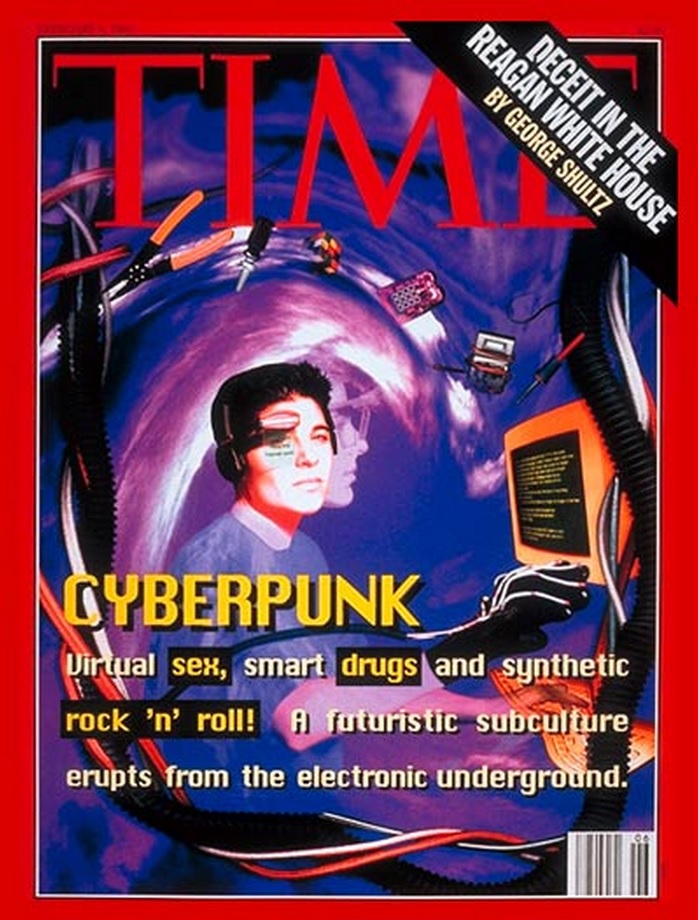

Still riding high in 1992, Mondo published Mondo 2000: A User’s Guide to the New Edge, a book containing 317 pages of compiled articles and artwork from past issues with new content mixed in. In February of 1993, Time magazine featured a “Cyberpunk” cover story, complete with art from Bart Nagel and numerous mentions of Mondo 2000. Cyberpunk had gone mainstream with Time’s article reaching households all throughout the USA. Much like Ron Rosenbaum’s “Secrets of the Little Blue Box” article published in Esquire in 1971, the Time article inspired hordes of new people to invade a subversive subculture. While Mondo received a boost from the story, it might have been a little too much attention.

Time Magazine’s February 1993 issue. Read the story here!

When Wired’s first issue came out in March of 1993, it was largely dismissed by the Mondo crew. In the eyes of many, it watered down the content Mondo was known for and passed itself off as a sub-par imitator. At the end of the day, Wired was appealing to a largely different audience. They didn’t need the hardcore console cowboys or smart drug pioneers to like them, they could get by with weirdo weekend warriors and flirt with the “normal people.” Mondo may have been a bellwether for the digital revolution, but it was on the decline. Many thought it was circling the drain.

Wired Magazine issue 1, March 1993.

Mondo 2000 was able to survive for another five years under the leadership of Queen Mu and her assistant-turned-editor Wes Thomas, ending with issue 14 in 1998. It may not ever be known if Mondo finally closed down due to infighting, failure to rouse advertisers, dilution of cyberpunk culture, or some perfect storm of those factors. Its legacy and influence, however, cannot be questioned.

Mondo 3000

In 2010, R.U. Sirius announced “MONDO 2000: An Open Source History”, a multimedia-driven Kickstarter project that attempts to capture the history and lore of Mondo 2000 — and all of its previous incarnations. Between a web document, a printed book, and video footage (that may ultimately become a documentary), Sirius hopes to save all of the stories, viewpoints, and ephemera that made Mondo what it was. He is currently in contact with past contributors, and continues to work on the project. In line with Mondo 2000’s whimsical nature, Sirius created a project reward that allowed one backer to be written into Mondo 2000’s history. Some of the events surrounding Mondo may not have happened, but all of them are true.

While we may not see a new issue of Mondo 2000 ever again, Sirius is hard at work. Within the last month, he has re-established Mondo’s Twitter presence and created a brand new website at mondo2000.com featuring reprinted and expanded articles from Mondo’s past, as well as new content.

For those who remember it, Mondo 2000 is something equal parts special and weird. For many, it changed everything, and then it faded into the ether organically as the world changed around it. Browsing the new site, my mind starts to wander. Maybe there is a void left in the world that could only be filled by Mondo 2000 coming back. Maybe the world needs a “Mondo 3000.”

Somewhere out there, hackers and cyber-mystics are typing away furiously on computers in coffee shops and bus stations, creating new virtual worlds and building communities.

Maybe someone else has already created a Mondo 3000.

Maybe this time I’ll be around to catch it.

Keep your eyes bulged and your cybernetic implants on alert for a follow-up article featuring an interview with R.U. Sirius.