Ghost in the Machine: Your Digital Afterlife

This article was originally written for and published at The New Tech on July 9th, 2013. It has been posted here for safe keeping.

On January 11th, Aaron Swartz passed away. If you’re not familiar with who he was and what he did, take a minute right now and look him up. A lot of focus was put on the circumstances of his death along with what he accomplished in life, and this seems to overshadow something that stood out to me: how to handle his legacy. Specifically, how he wanted his legacy to be handled.

Swartz created a simple web page in 2002 about how to handle things if he were to be “hit by a truck.” Who would take over his website? Where would his source code end up? He created an electronic will. The idea of a will is nothing new. Most people create a document outlining how their assets will be divided up when the time comes- it just makes things operate more smoothly. But what about in the electronic world? Surely we mark who will get our house but what about who gets our website? It sounds amusing to think about or even entertain the idea. We allocate or physical property, things that can be defined in dollars and cents, but hardly consider our intellectual property.

If you haven’t had a Facebook friend pass away yet, you’re likely in the minority. It’s sad, of course it’s sad, but it needs to be talked about. If you have ever had a Facebook friend pass, you may observe a cycle where his/her profile is used first as a memorial and then eventually deactivated all-together. These are my experiences. I understand and empathize with the feelings of the family in these circumstances, but to me this seems a little like burning all of a loved one’s possessions with the ease of a single mouse click.

These are the two ends of the spectrum.

It’s important to let go and move on, but it’s also important to remember and honor. In a basic sense, I apply the same fundamental ideas towards the death of a person as I do towards that of a technology. Most are quick to push the old out of thought, but the few make a move to preserve. I preserve. It’s just my nature.

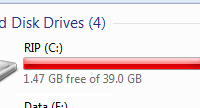

Swartz’s situation resonated with my own beliefs. If I were to be hit by a truck tomorrow, what would happen with my stuff? My digital stuff. I run a fair number of websites, I rent a VPS and a dedicated server, and I have bills, Amazon S3, service subscriptions. If I go, they eventually do too.

I’d like to tell you that I have a contingency plan, but I don’t. I haven’t reflected fully on the logistics of it. Could I think of people to take over my digital stuff after I’m gone? Of course, but would they want to? When someone dies and it becomes your responsibility to handle their belongings, it’s not typically a drawn out process. You keep some stuff, you toss some stuff, but you don’t normally end up with something that needs to be maintained and worked through. Websites take a fair amount of time and money. Storage, while getting cheaper, is still expensive for the hobbyist. There’s unavoidable maintenance.

That said, I would hope that my online persona remains long after I do. Forum accounts, Facebook information, Twitter posts, etc. should survive as long as possible. I want everything to be available to anyone who needs it. Hand over my source code and pick apart my log files.

Open source my life.

If I’m not going to work on it anymore, I’d like to give that ability to anybody who is interested.

To have these things removed, stripped from the world, is just nonsensical to me. Someone’s interesting and original work disappearing because nobody knows how to or doesn’t want to handle handle it? Nothing upsets me more than something like that. It’s akin to tearing pages out of every history book. In our modern world, people are quick to think that things last forever. Digital artifacts can go missing overnight.

We shouldn’t be worried so much anymore about having something embarrassing stored online forever, we should be more worried about something important disappearing tomorrow.