The Brain Mutator For Higher Primates — A bOING bOING Retrospective

This article was originally written for and published at Neon Dystopia on June 13th, 2018 It has been posted here for safe keeping.

In 1988, Mark Frauenfelder and his wife Carla Sinclair started a small zine out of their apartment in Sherman Oaks, California. This wasn’t a full-time job for Frauenfelder, who studied mechanical engineering in school and worked professionally designing hard disk drives during the day. The drudgery of his work got to him, and he desperately needed a creative outlet, and that outlet would become bOING bOING.

Frauenfelder was fascinated by self-produced magazines of the time like Screamsheet and Reality Hackers, which in many ways acted as a precursor to amateur websites and blogs that permeate the Internet today. Zines were a bit different than the magazines you may pick up in a corporate bookstore. They were rough, uncensored, and often handmade by a group of amateurs having fun. Maybe you’d find some on a table at a trendy coffeehouse, or maybe the employee bathroom at work, but more often than not you would have to seek them out by mailing cash to the creators and hoping they sent something back. This wasn’t the first foray into publishing for Mark, who had created two issues of a mini-comic called Toilet Devil, and a one-issue zine titled Important Science Journal some time earlier. This new zine would be different. It would be for cool things, cyberpunk, wacky stuff, high weirdness, and anything downright crazy the husband and wife duo found interesting.

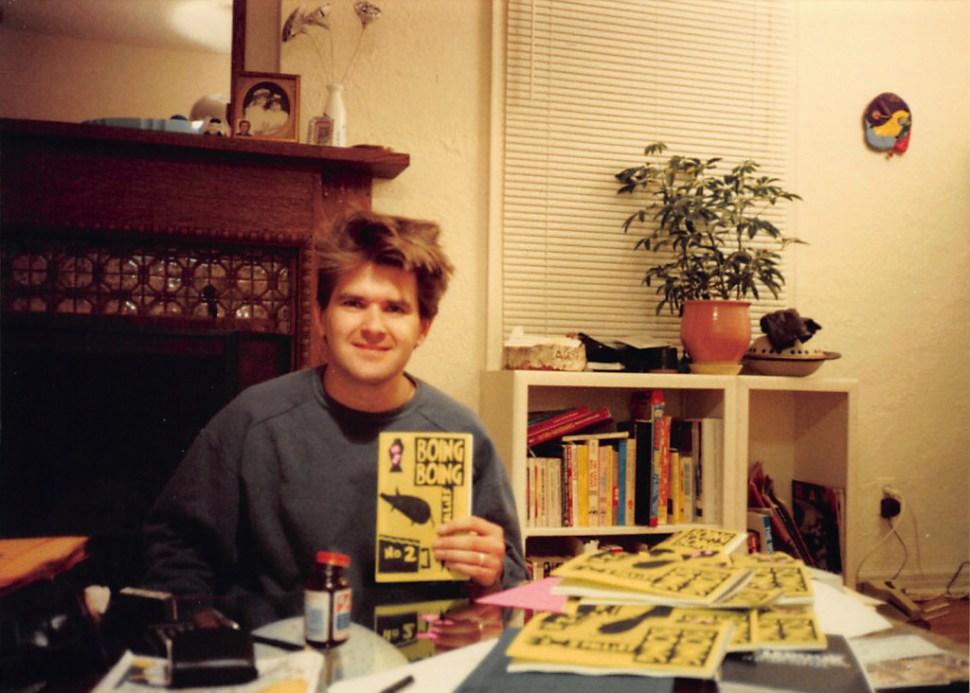

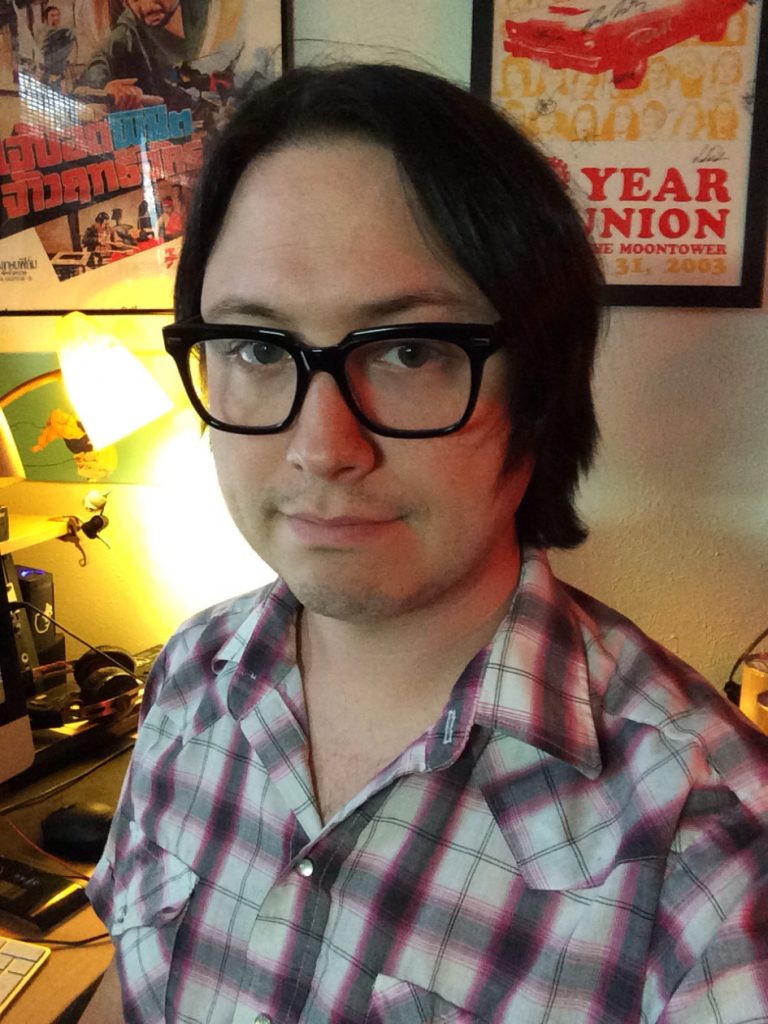

Carla Sinclair and Mark Frauenfelder.

Frauenfelder, an avid punk rock fan, enjoyed music by acts like The Ramones and The Clash throughout his youth. When asked what he liked about punk music during a 2011 interview, Mark responded, “It was the DIY aspect of the punk culture. You didn’t need to have expensive equipment or a record contract. I also liked the primitive sound. It’s hard to say, but as soon as I heard it, I loved it.” In many ways, the new zine would mirror punk culture and the DIY aesthetic: it wasn’t perfect, there wasn’t any backing or stability— it was raw and unfiltered and noisy and fun.

As a child, Frauenfelder was drawn to computers and comics, which eventually inspired his love of all things geeky and his fascination with alternative media. He first learned about zines from the Winter 1987 issue of Whole Earth Review titled “Signal” (co-edited by Kevin Kelly, who would later be among the founders of Wired magazine) in which an article explained the concept of zines and even mentioned a zine directory (which was actually a zine itself!) titled Factsheet Five. Frauenfelder ordered a copy and immediately sent away for as many zines as he could.

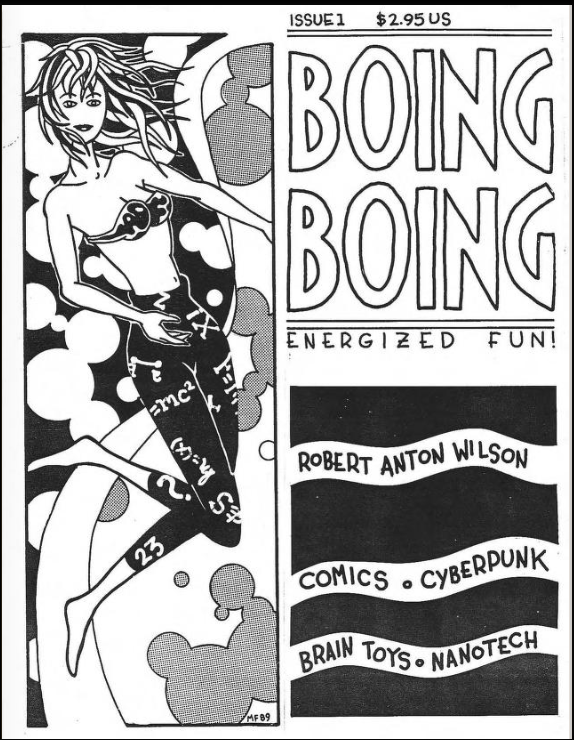

The first issue was layed out before the pair needed to move to Boulder, Colorado in 1989. Carla took on the role of editor, which she would retain for the run of the magazine, while Mark settled into the co-editor/publisher position. Packed full of cyberpunk sci-fi, underground comix, and mind-altering media, Carla xerox’d about 100 issues of the 36-page zine, and began to distribute it. The first issue was a trip: there was an interview with futurist Robert Anton Wilson, a comic about taking LSD, and a libertarian-cyberpunk manifesto titled “Crossbows to Cryptography: Techno-Thwarting the State!”, amongst others. bOING bOING, the World’s Greatest Neurozine, was born!

bOING bOING issue 1 (1989) cover. Read the whole issue here.

Stop right there. I can already see the candy-colored cogs in your brain cranking away trying to understand the text you just sucked off the page. bOING bOING… as in Boing Boing… as in boingboing.net, the popular group blog that arguably pioneered blogging as a concept in the early days of the Internet. Few people know that Boing Boing started its life as a humble zine, printed on dead-tree paper— not electronic bits ethereally whirling around the ’net. Boing Boing may now be a staple of the Internet for those interested in science fiction, futurism, technology, and left-wing politics, but 30 years ago, it was a brand new zine called (and stylized as) bOING bOING.

bOING bOING stayed in Colorado for several issues and were hitting their stride as distribution ramped up. They refined their manic, madcap, eclectic style to become the premier net rag, full of punk attitude and sassy style. While the first issue of the magazine featured content from a handful of technoid misfits, the contributions were soon creeping in from all over. Back before the Internet, zines had to rely on a combination of luck and word-of-mouth to be successful. You could distribute copies of your zine to your friends, send them to other zines you like in the hopes that they’d review it, or trade them with others to spread far and wide. If it was any good, you’d have insatiable, bug-eyed mutants clamoring for more. If it was bad, it would fizzle out, and be all but lost to time. Early contributors for bOING bOING included science fiction authors like Paul Di Filippo and Rudy Rucker, as well as cyberculture writers and zine editors like Going Gaga helm Gareth Branwyn and FringeWare Review wizards Paco Nathan and Jon Lebkowsky. Within the zine microcosm, bOING bOING was a hit!

Mark Frauenfelder pasting paper together to assemble copies of bOING bOING issue 2 (1990). Read the whole issue here.

It is important to understand just how much cyberpunk influence bOING bOING was amassing in this early period of publication. Just three years before bOING bOING’s first issue, Bruce Sterling edited the acclaimed Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology (1986), featuring short stories by prominent, front-wave authors in the cyberpunk subgenre. bOING bOING would go on to feature articles by authors from this anthology such as Rudy Rucker, Marc Laidlaw, Paul Di Filippo, John Shirley, and even Sterling himself. Others such as William Gibson and Lewis Shiner would ultimately be interviewed. Di Filippo in particular would even use bOING bOING Second issue as a launching point to share his ideas on a half-serious new subgenre he was developing called “ribofunk,” a blend of “ribosome” and “funk” (a direct response to “cyberpunk”), that acted as a prototype for what we would later come to call “biopunk.”

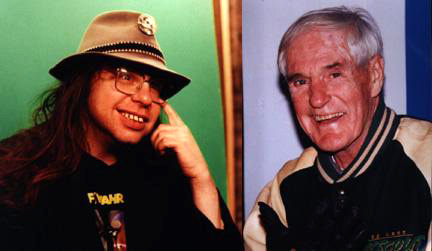

Around the time that Mirrorshades was hitting hardback, before bOING bOING launched, Mark and Carla would run into R.U. Sirius and Queen Mu selling the poster-sized second issue of their High Frontiers zine (a psychedelic counter-culture zine which would eventually morph into the cyberpunk Mondo 2000 a few years later) at a Timothy Leary show in San Francisco. Frauenfelder vividly describes the duo by stating “RU was this grinning hobbit-looking character with a floppy hat with a Andy Warhol button on it. Queen Mu was a very delicate blond woman with Stevie Nicks clothes and granny glasses and she [had] a permanent blissful smile and didn’t say much.” After buying a copy of their zine, Mark and Carla would attend High Frontiers Monthly Forum events in Berkeley thrown by R. U. and Mu, eventually meeting like-minded cyberpunks and tuned-on mutants such as author Rudy Rucker and future Mondo 2000 art director Bart Nagel. The friendship between the group grew, with both Rucker and Sirius eventually writing for bOING bOING.

R.U. Sirius and Timothy Leary.

bOING bOING covered culture in a no—holds-barred way. No topic seemed too taboo or salacious or untouchable. Drugs, kinky sex, and absurd humor littered the pages— sometimes comprising the entire issue. You could get the latest news about the ’net, independant comics, goth culture, punk music reviews, and everything in between. You might see a cyberpunk short story sharing a spread with a Schwa alien cartoon or recruitment advertisement from Church of the SubGenius. bOING bOING dripped with Gen X culture, and as with Frauenfelder, appealed to those fed up churning in a stuffy office all day or burning out in their McJob. bOING bOING, like a lot of technology-soaked publications of the ’80s, followed a natural evolution with roots in the counter-culture movement of the 1960’s. Instead of the dirty, free-loving and peace-wheeling hippies, bOING bOING was more in tune with the punks of ‘77 who scornfully rejected the old political idealism and subconscious with a rebellious, no-bullshit attitude. Music, culture, and technology were getting more personal; the milieu was different. The average bOING bOING reader was more likely reading Amok Dispatch (1986) rather than the Whole Earth Catalog (1969), and listening to Black Flag instead of the Grateful Dead. Kerouac made way for Coupland. This was something new— this was theirs.

For issue eight, their first with full color, Frauenfelder and Sinclair moved back to California. They didn’t stick around in one place for too long, pin-balling from Hollywood to Los Angeles to San Francisco, and eventually back to L.A. throughout the remaining years of the zine. bOING bOING was booming throughout this period, and benefited from an influx of cash attributed to Mark being employed to design Billy Idol’s Cyberpunk (1993) album. While in Los Angeles (the first time), Frauenfelder was offered a job as a writer at a small magazine startup, also run by a husband and wife team, called Wired. “They saw Boing Boing and they really liked it,” Mark has said previously, “so they called me up and asked if I could come work for them as an editor and inject some of Boing Boing’s sensibility into the magazine.” The couple relocated to San Francisco, and set up bOING bOING on the first floor of the Wired building, then located at 544 2nd Street.

Wiley Wiggins who you may remember as Mitch Kramer in Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused (1993) was also actively involved in early ’90s cyberculture. He wrote for bOING bOING as well as Mondo 2000 and FringeWare Review.

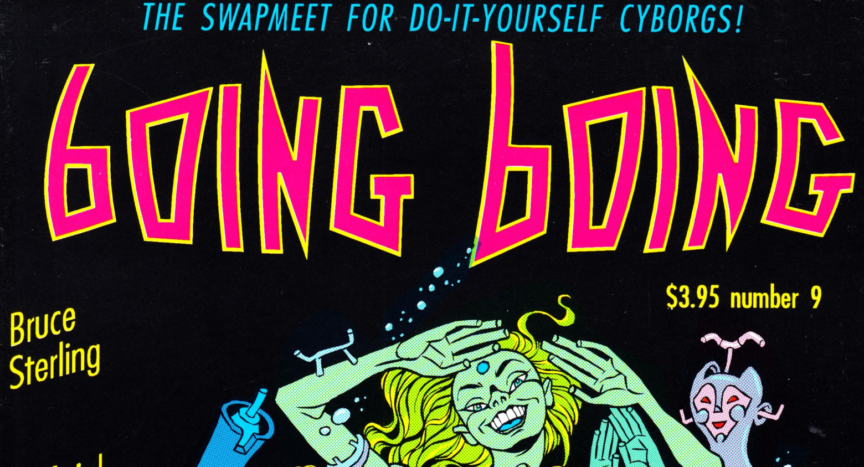

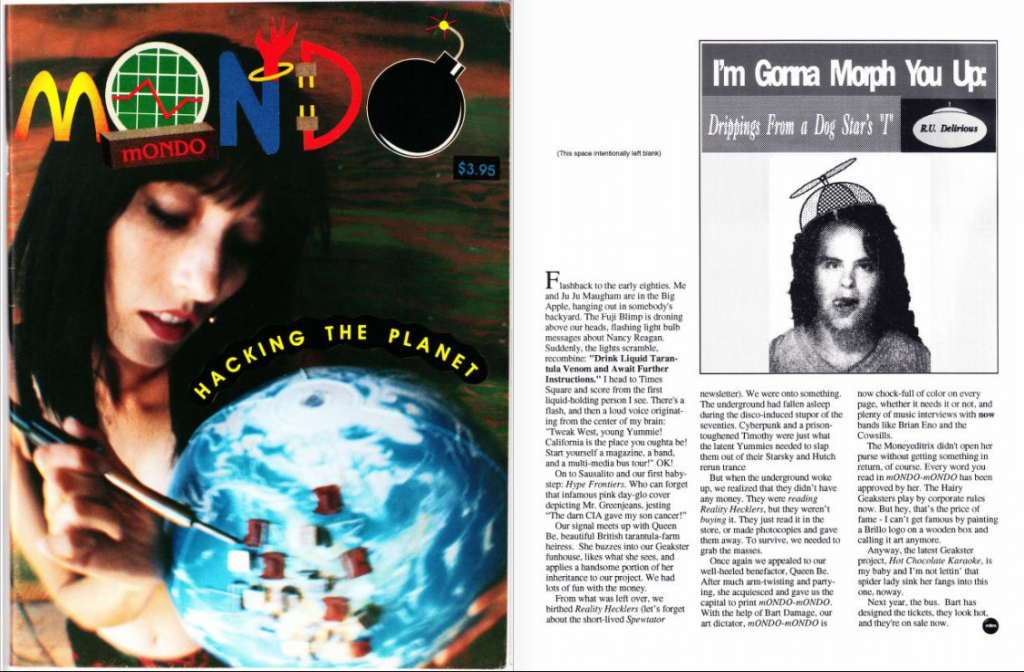

Wired released its first issue in 1993, but before that, it was just a group of writers and publishers trying to throw together a new concept for a generation of MTV-watching punks, immersed in the fresh world of cyber-culture. Publisher and co-founder of Wired, Louis Rossetto, pitched his magazine concept by saying, “We’re trying to make a magazine that feels as if it has been mailed back from the future.” This fit in nicely with Frauenfelder’s style. The Wired building was truly a melting pot of San Francisco culture in the early ’90s. Wired had recently moved from the first floor, a large, open, warehouse-like space, to the second floor when it needed something roomier. bOING bOING moved into Wired’s old digs in the corner of the gigantic room, which was already buzzing with activity from other independent zine makers in the Bay Area. Other publications sharing the space included Dave Egger’s Might (a magazine aimed at Generation X), Just Go! (a travel magazine), Hum (a magazine for young South Asians), CUPS (a more eclectic culture zine), and Star Wars Universe (I think you can figure this one out). Mark continued to work on bOING bOING while also netting income from the burgeoning Wired, though Carla took over most of the production at this time. Issue 9 of bOING bOING would become notable with such content as an interview with Bruce Sterling about his new book The Hacker Crackdown (1993), a regular music column by Richard Kadrey, and a 7-page pastiche of Mondo 2000 (starting on the back cover, so it actually looks like a Mondo 2000 issue when upside down) featuring articles with titles like “I’m Gonna Morph You Up,” and “Virtual Neural Jacks.”

Cover and first page of the mONDO mONDO parody in bOING bOING issue 9 (1992). Read the whole issue here.

By this time, issues began to feel more and more refined— both in content and physical appearance. Once printed on cheap paper, the zine now had dazzling, glossy covers, and was filled with content from a loyal band of the fringe-elite. bOING bOING never seemed to lose its quirky, geeky, out-there edge that had been so crucial in cultivating the zine’s culture and feel. At its peak, bOING bOING reached a circulation of 17,500 issues. Unfortunately, nothing lasts forever.

By 1995, bOING bOING would release what many might consider its last “regular” issue, though the year also marks what many would say is a much more crucial event for bOING bOING: the launch of its website, which we can still visit some 23 years later. Behind the scenes, the independent printing industry was changing for the worst. In 1994, shortly before this penultimate issue of bOING bOING was released, the two largest independent magazine distributors in the country went bankrupt. bOING bOING ended up losing about $30,000 because of this, causing delays in the production of another issue. While the launch of boingboing.net may be seen as a deathblow to the zine, it might have actually been the only thing that saved it. It was clear that publishing on paper was not going to be a long term solution. Publishing on the ’net could be done for free.

The print zine may have been fading, but that doesn’t mean the culture built around it was left to decay. 1995 became a year of handbooks. Aligning with The Real Cyberpunk Fakebook, a satirical cyberpunk handbook written by select Mondo 2000 staff, Frauenfelder, Sinclair, and bOING bOING regular Gareth Brawnwyn collaborated on the 205-page Happy Mutant Handbook, a guide to offbeat pop culture. Sinclair would also release her first book, Net Chick: A Smart-Girl Guide to the Wired World, an optimistic yet sassy guide for women carving out their place in the early days of the web. Further, Frauenfelder was continuing to work for Wired where he would attain the position of editor. bOING bOING ultimately released its final print issue, #15, in 1997 after a two year hiatus. Unlike previous issues, this one more closely resembled a book, with more standard binding and a squarish appearance; the contents however were the same weird and wacky that bOING bOING was known for.

The Happy Mutant Handbook (1995) was actually designed by Georgia Rucker, author Rudy Rucker’s daughter! Read the whole book here.

Frauenfelder would eventually leave Wired in 1998, following his tenure there with a stint as the “Living Online” columnist for Playboy from 1998 to 2002, a job he was recommended for by Playboy editor and former zinester Chip Rowe (who had published Chip’s Closet Cleaner in the early ’90s). Later, Frauenfelder would become editor-in-chief for Make: magazine, a DIY/hobbyist bimonthly, while also producing a few books before settling into a role at the Institute for the Future as a research director. He also serves as Editor-in-Chief and podcast co-host with Kevin Kelly (again, of Wired and Whole Earth Review fame) at Cool Tools, a site about the tried-and-test tools and gadgets. Sinclair would later publish a technothriller, Signal to Noise (1997), and become editor-in-chief of a Make: spin-off magazine titled Craft: which ran from 2006 to 2009. Frauenfelder still maintains top position on the boingboing.net masthead, along with bOING bOING zine regular David Pescovitz. Carla has contributed to the site as recently as 2016, but additional writing is currently provided by Cory Doctorow, Xeni Jardin, and Rob Beschizza.

In May 2011, Frauenfelder would publish a bOING bOING anthology of favorite interviews from the zine era in a free, online-only PDF file. “The first few issues of Boing Boing had print runs in the low hundreds, and the biggest was 17,500 copies. Today, the blog easily gets that many page views in an hour,” Frauenfelder states in the the article announcing the anthology. The zine may be gone, but its legacy lives on through boingboing.net. “I think I’ll always be involved in some media. Who knows what Boing Boing will evolve into. But, I kind of imagine that it might not be too different than it is now,” Frauenfelder says in a 2012 interview, “I see myself continuing to make Boing Boing into an even better experience for its audience.”

For me, it can’t get much better than a three-color zine made by a husband and wife team exploring the weird and wonderful world. I only became aware of bOING bOING a few years back when I was searching for issues of Mondo 2000, and stumbled upon it quite accidentally. Before long, I was able to track down almost every issue and began to scan them, page by page, in an attempt to save them for future generations. I never did find the first two issues for purchase, but luckily I uncovered some PDFs of them online that were scanned at some point by Frauenfelder himself many years ago! After my scanning was complete, I uploaded each issue to the Internet Archive where you can download or browse them today, completely free. I’ve been lucky enough to have a few interactions with Mark Frauenfelder online after this, and he’s always been quick to answer my obscure questions about the old days and provide new insights. bOING bOING, the zine, remains a point of pride for him and he seems to love sharing it. It was and is something he loved, and he was there to see it mutate, evolve, and grow over time, while he did the same.

The print is dead, but the brain jack is warm. You can always go online.