On Music, Mondo, & Mayhem: An Interview With R.U. Sirius

This article was originally written for and published at Neon Dystopia on September 1st, 2017. It has been posted here for safe keeping.

I recently wrote an article for Neon Dystopia on Mondo 2000, a cyberculture magazine that helped shape the cyberpunk sub-genre. When thinking of Mondo, the first person that comes to mind for most people is Ken Goffman, better known as R.U. Sirius. While he may be best known for his time at Mondo 2000, Sirius has no shortage of interesting accomplishments. Aside from Mondo, Sirius has had articles published in Artforum International, Rolling Stone, Time, Wired, and Esquire. He has been editor-in-chief at Axcess Magazine, GettingIt.com, and H+ Magazine. He’s hosted two podcasts, started multiple websites, and even had a run for the presidency in 2000 under the Revolution Party. Did I mention he has also authored or co-authored 10 books and appeared in two movies?

R.U. Sirius (Photo by Bart Nagel).

Aside from his accolades, Sirius is known as a knowledgeable, iconic, and somewhat eccentric guy. An acquaintance of his once stated, “[Sirius] once told me he had trouble reading anything written before 1990-it was 1980 at the time.” While Sirius has constantly been seen as being ahead-of-the-curve in a lot of ways, it was never something that hindered him — it only helped him excel. Without R.U. Sirius, we may have had a completely different experience traversing the digital revolution. At a minimum, it wouldn’t have been nearly as fun.

I had the pleasure of interviewing R.U. Sirius for Neon Dystopia over the course of the last few weeks while working on the Mondo 2000 retrospective. Being able to pick his brain was an experience, and after he answered my long series of questions, he started to tell me about his music — something I wasn’t at all familiar with. I had known R.U. Sirius the editor-in-chief of Mondo 2000, but not R.U. Sirius the musician. With a little research, I discovered he was the lead singer and songwriter for the band Party Dogs, which performed in New York in the 1980’s. Later in the 90’s, he would perform in the band Mondo Vanilli, which even signed a record deal with Trent Reznor’s Nothing Records (though there was never an official album release). Sirius recommended two albums to me, and I queued them up as I sat at my keyboard and pulled at the seams of Mondo.

The first album he recommended to me was MONDOtoxicated, a work-in-progress collaboration with psychedelic jamtronica band Phriendz. Sirius does the lyrics and has vocals on all but one song in the collection, “I Hope You Didn’t Dose the Pudding,” which instead features Phriendz’s own Daddy Phriday. The first track on the album, “Speed and Weed” is a great entry point into the unique sound put out by the collaboration. You can feel the funk and electronica elements, and they blend together seamlessly to create something otherworldly. Later in the album are two remixes from Sirius’s Party Dogs days: “On The Beam,” and “President Mussolini Makes The Planes Run On Time.” These songs are very punk-fueled, beckoning back to their original 1982 compositions, but blend well with the new electronic elements in the remix.

The second album, a much longer compilation spanning from 1982-2010+ titled That Which Does Not Kill Me Makes Me Hipper, features songs from Party Dogs, Mondo Vanilli, collaborations with Phriendz, and also songs by band SLT which Sirius supplied lyrics for. Aside from the Phriendz collaborations (which were also featured on the other album) the Party Dogs songs have a great punk rock sound that I could listen to all day. The real standouts on the album are the the techno-rock Mondo Vanilli tracks. “Love is the Product” in particular is a playful, satirical song that will get stuck in your head with its catchy chorus. While the album spans a number of decades and a few different genres, Sirius’ style shines through on each track. You are able to see how his music has evolved over the years, and never loses its power or passion.

While listening to these albums, I got the sense that music was and is an important part of Sirius’ life. I had to rethink my interview and go beyond the Mondo topics I was so focused on. I wrote back to pester Sirius with some additional questions, this time about his musical career.

Below is the full interview, with all of the questions on Mondo 2000, music, and everything else mingled together. Take a ride, and try not to fall off!

Neon Dystopia: Before you started working on High Frontiers, you were in a band called Party Dogs. Was this your first foray into music? How did you get involved in the band?

R.U. Sirius: Party Dogs was my first real foray. I recorded 3 songs before that with a band we called The Spoons as vocalist and lyricist in an analog electronic music room at a State University in Binghamton NY in 1976 – two of them got some local airplay. The song “Reggae Ripoff” caused a minor stir when a DJ who liked to play it realized I was a local white boy and freaked. The lyrics are here. But there were no live appearances.

I had a few onstage moments after that… I’d go onstage for one song basically… “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” (or “Raw Power”, once). But Party Dogs was the first sustained band that actually performed often. Actually the only band that performed often.

I was in Brockport New York, a small college town. I’d gained confidence in my voice by learning the entire Stones catalogue with a friend who thought he was Keith Richards (RIP, it goes without saying) … and when the neighbors came by saying they thought it was the Stones record and then realized we were doing it … I think that was my breakthrough in terms of confidence. I was already 25.

So I started putting together a band in Brockport. The first one we called Skippy and the Nice Guys. It was raw and confrontational. Everybody hated it.

When Party Dogs started, almost everybody hated that too… but we got good with practice. It was more punk-inflected rock than punk. Among our copy songs we played the Dead Boys, Sex Pistols and Iggy. But on the other hand, we played some Rolling Stones and Bowie. And mostly our own songs, of course. We ended up being kind of popular both in town and in Rochester, New York nearby. The other guys continued being in great bands in Rochester, including SLT, who I wrote some lyrics for a few years ago.

At our last Party Dogs appearance in Brockport, we closed as usual with a noise rock version of “Strangers In The Night.” Some jocks who were tripping on acid decided I was the devil and plotted to kill me. A girl who knew them and knew me talked them out of it!

ND: Music seems to be a big part of your life. Do you see yourself as a musician at heart despite all of the other work you’ve accomplished?

RU: There’s a great line in the TV show_ _Dear White People… “Trust me. Find your label.” I guess I’m kind of too cosmic when it comes to considering myself anything. I’m amused by the way many millennials have this really expansive panoply of labels (particularly for sexuality) but such a constricting need to be codified.

Having said that, to the extent that I made a livelihood, it was mainly as an editor-in-chief and a writer.

I’d love to be known for my lyrics… like maybe Van Dyke Parks or Bernie Taupin or Pete Brown (Cream)… except I guess mine are much weirder. I don’t know. Who writes lyrics for avant-garde operas? I’d like to be him or her!

Mondo Vanilli album cover for i.o.u. babe.

ND: Have your influences changed dramatically between Party Dogs, Mondo Vanilli, and your most recent music?

RU: In terms of vocals, I’ve looked to people who work with rhythm and attitude but don’t have a vast range — Lou Reed, Jagger… for some examples. And just before I embarked on my latest work, I had a cough that lasted for 2 months. I had kind of a recent-Bob Dylan growl befitting of an old man whose done a few naughty things… but it disappeared. I don’t know if I will ever regain my voice the way I want it.

In terms of lyrics, it’s just whatever comes. I think maybe Frank Zappa is an influence although I’d maybe rather write like Leonard Cohen or Nick Cave. But I think my stuff is mainly unique and as good as almost anyones… can I say that? I mean, for permission to go off the map of the usual rhyme schemes… I’d look to Don Van Vliet, Patti Smith and Bowie.

ND: In Mondo 2000, and earlier with Reality Hackers and High Frontiers, I see hippie/yippie influences, such as the work Stewart Brand was doing with the Whole Earth Catalog. I also see some parallels with Ted Nelson’s work, and the sort of general DIY attitude that the punk subculture perpetuated. What would you say were some of the biggest influences that Mondo 2000 drew from?

RU: I view the influences in terms of periodicals more than in terms of hippies or yippies etcetera, although a kind of counterculturalness is intrinsic. For myself, and I think for many others involved in the publication, there was a love of magazines.

Mad Magazine was as much an influence as Whole Earth.

Creem magazine with its irreverence… it’s disrespect for journalistic conventions and lack of rock star worship.

Some Dadaist publications like File (which became Vile after punk rock hit) for its use of allusion and not having to make sense.

The original underground papers of the late ‘60s/early ‘70s for their aliveness – trying to transcend their containment within a printed thing that you can buy and hold in your hand and have expectations towards. Can we make this object explode or dance or shoot off psychedelic sparks?

Interview… because it used interviews without the intrusion of the all-knowing authorial voice.

Omni for the pop science and technology and for recognizing that was the next cool thing.

Evergreen for counterculture in an urbane package with top tier writers like Terry Southern, Susan Sontag, Tom Wolfe, Eldridge Cleaver.

Wet for looking cool and feeling futuristic

ReSearch/Search and Destroy for exploring the connection between punk counterculture and various historical/anthropological memes like Situationism, body modification and so on.

That’s off the top of my head.

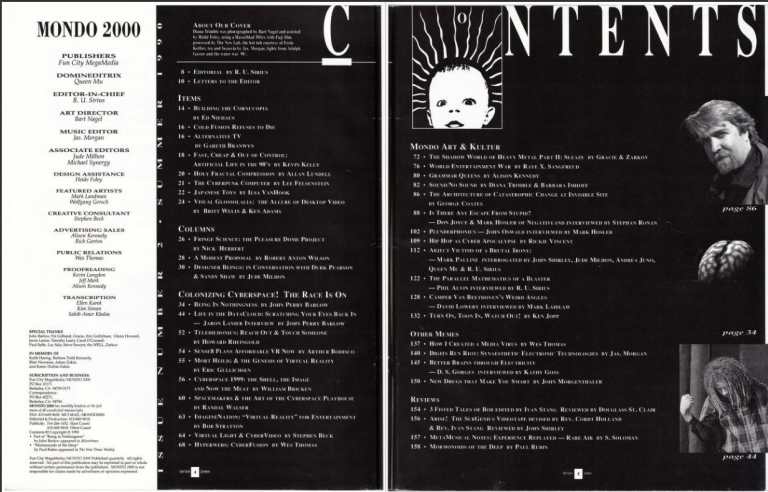

ND: What was the typical content of an issue, was anything too far out to be included?

RU: There was some relatively straightforward reporting on tech and science developments towards the front, usually … right after the very colorful and strange letters to the editors. Lots of interviews and conversations with people making up the hipper edges of the emerging tech culture but also musicians and just eclectic off-center stuff like an art forger/money counterfeiter. I mean, I can’t really do any issue justice in terms of how ultra-strangeness rubbed up against techie relative-normalcy.

I can’t remember a feeling that anything was too far out to be included. They were different times. The extremes hadn’t been fully weaponized yet, so to speak.

Mondo 2000 issue 2 contents.

ND: The 1980’s saw a big push into science fiction and the development of cyberpunk with Neuromancer and the growing popularity of publications like OMNI. Were you aware of the content in this space?

RU: Yeah we were friendly with Dick Teresi and other editors at Omni. We were excited with SF Eye and some other publications I’ve forgotten since. The excitement over the so-called cyberpunk writers was hitting us when we were still High Frontiers (the magazine we published from 1984-1988, preceding Mondo). Timothy Leary was very excited about Neuromancer, so he kind of led us towards that, but we had people around like St. Jude Milhon who were already trying to call our attention to that. There were some cool periodicals doing something sort of vaguely similar that came and went. And Boing Boing preceded Mondo technically, although we had already done High Frontiers and Reality Hackers and they were influenced by those.

ND: Mondo 2000 is often cited as a large influence in the development of the cyberpunk subculture. How do you think it has been able to influence cyberpunk over the years?

RU: I think Mondo was more its own thing. Anybody who took cyberpunk too seriously as a movement or a memeplex might have been alienated by our eclecticism, our fancy design, our not-giving-a-fuck about cyberpunk or much of anything mien. The hardcore nerds and cyberpunk sorts, for instance, hated that we did fashion spreads and girls with circuit boards around their nipples (as did some feminists). Mondo was an art project, really, specific to the people engaged in it, with the idea of cyberpunk or cyberculture in the nose cone but so much else going on behind it. And yet we hit a sweet spot for other eclectic sorts… I guess I’d say hipsters, in a positive sense (that label wasn’t a curse back then.) But also, the sort of person that loved Robert Anton Wilson and Church of the Subgenius.

ND: Tell me about the culture of the Mondo 2000 house. What was a normal day like? How would you describe the parties?

RU: It was a largish house in the Berkeley hills… looked like a Blue Oyster Cult cover… thus called a “technogothic citadel” in various reports. There was a dead red 1956 MG out front.

The upstairs front room was used as the main office. Three people would roll in and start answering phones at around 9:30 am. Andrew Hultrkans our managing editor tended to come in early too. I slept in a room downstairs with my girlfriend at that time… we made some noise in the morning hours that would “frighten the horses” upstairs. I came upstairs in a silk bathrobe and nothing else usually around 11 am and went into the kitchen to make coffee. Bart Nagel, Heide Foley and the art department was in a large downstairs room. I don’t know when they started but they often worked far into the night. The place was pretty dedicated to working on the magazine and dealing with the business and publicity on weekdays. Sometimes people would show up… Jesus Jones (a “rock star” of the ‘90s); Buffy Saint-Marie! She’s awesome by the way. Some kids looking for me… the main dude said his dad was head of the CIA or something like that.

I don’t know that I want to describe the parties. Some of them were large… lots of people. I don’t remember any outright orgies – despite hearing rumors about them. Massive psychedelic drug taking was more common during the High Frontiers period in the mid-‘80s. There was tech being shown off… brain toys, definitely some drugs, sex in private places… I have this memory from around 1991 of these ravers being really contemptuous that the old folks were “dancing to Bryan Ferry.” But it wasn’t Bryan Ferry. It was Roxy Music and they were way fucking better than anything EDM ever produced!

Editors Rudy, Queen Mu, Ken Goffman, with Bart Nagel, the graphic designer. (Photo by Bart Nagel.)

ND: I often think that Mondo 2000 benefitted from hitting at just the right time, as computers and technology were riding this sociopolitical wave in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Do you think that Mondo 2000 was just as influential at the time as it was reactive? What was the feedback loop like?

RU: I think Wired hit at just the right time to be commercially successful (they were, of course, more accessible to the “normies”). We intentionally teased out the countercultural influences in the early Silicon Valley digital culture and helped make the connections between alternativeness and technoculture. A fellow named Michael Gosney – who had a digital arts magazine called Verbum – sponsored something called the Digital Be-In, timed to the annual Mac gathering in San Francisco, independent of us… so there were other people doing this as well. (We attended those splendid events, of course.)

San Francisco counterculture’s embrace of the celebrations of technology, virtual reality etcetera at that time in the early ’90s is kind of an extraordinary thing that requires a whole other essay. It was a culture where the people who throw rocks at the Google bus would have been at the same party as Larry and Serge… our party! Anticipating the future brought people together more than the actual thing.

Cover for Verbum issue 5.2. Click here to read the whole issue.

ND: Why do you think Mondo 2000 was so successful at the time? What did it have that nothing else did?

RU: We had a lot of hype from the mainstream media … an excitement about the superficial stuff like VR and smart drinks… that helped to let people know we existed. But I think the magazine itself was something extraordinary. It was the message from some other planet… some other future… that Wired later claimed to be. And there was an audience that wanted that. People used to haunt magazine stores, Tower Records, in various towns… “When will we see another issue of MONDO 2000.”

I mean, it wasn’t that successful. We hit our peak just shy of 100,000 circulation.

ND: Timothy Leary once said that Mondo 2000 was “a beautiful merger of the psychedelic, the cybernetic, the cultural, the literary, and artistic. It shouldn’t last a long time.” Do you think that Mondo could have gone on for many more years, or was it by nature much more fleeting?

RU: 2000 would appear to be an expiration date. It could have continued. There were some internal problems that I don’t want to air here. Wait for the book, still in progress. We could have charted a new course of outrage. We had a lot of opportunities in terms of advertising that weren’t used… but I’ll leave it at that

ND: I often look back at the comic “The Guy I Always Was” by Patrick S. Farley and consider how Mondo 2000 was more of a publication that invented the future (in both a dreaming sense, or simply making things up) instead of simply reporting on it. Do you think that would be an accurate way to put things?

RU: Yeah it was saying this thing was happening and then helping it to actually happen. Except for the things that didn’t happen, like universal virtual reality and “sharpies mutants and superbrights” taking over the planet… I mean, it was a fantasy of the total transmutation of everything… and it’s turned out to be more the total fragmentation of everything, although we always made sure to predict that too (just in case.) I mean, it wasn’t really all that message-driven … there were lots of pages and lots of varying views and visions and just plain fun.

By the way, I love that comic.

H.M. Ludens, from “The Guy I Almost Was.”

ND: A lot of people attack Wired magazine though accusations that they copied Mondo’s style and watered it down for a broader audience. Do you think Wired was ever able to bottle the Mondo 2000 spirit? Was their success just a matter of timing based on when they started?

RU: They used a lot of the same writers and covered some of the same stories at first, but the appeal was more towards the ordinary… They were genre specific. They didn’t have interviews with Daniel Johnston or Diamanda Galas or gonzo anthropological theorizing about secret cultic uses of tarantula venom as an intoxicant… stuff totally outside the supposed techno genre. They had a conventional approach that hit a bigger audience and was comfortable for advertisers.

They weren’t trying to bottle the Mondo spirit. The writers were told explicitly to steer clear of counterculturalness… Alternativeness was just the colored sprinkles on the corporate frozen yogurt. Negativland pranks were cute items where for us they were subversive blows against the empire … and the main article. I mean, they were probably right. The empire survived our culture jamming … and now the alt-right establishment is doing a form of it themselves. None of this is meant to be all negative about Wired. They did what they did well and I enjoyed many of their issues… and even wrote a few bits.

ND: Are there any people from the Mondo 2000 days that you still keep in touch with?

RU: I’m in touch with many of them. St. Jude Milhon, who I worked closely with, died in 2003. Our business manager, Linda Murman, died of cancer maybe a decade ago. Kathy Acker, who was a friend to all of us, also died of cancer. There have been losses like that. A lot of people have been interviewed for the Mondo history project. I’ve been in touch with many of them.

ND: One person from the M2K staff that has always intrigued me is Michael Synergy, especially with his quick-fire claims of government-toppling knowledge in the Cyberpunk (1990) documentary. Do you know anything about his activities after Mondo 2000? Did he indeed mutate and take over the world?

RU: That’s a complicated and difficult subject. He disappeared after failing to appear at his wedding, more or less. Howard Rheingold swears that he’s Michael Wilson, who was involved in the development of the TV show Burn Notice and that the main character was based on him or at least on his braggadocio. There are some strange, disturbing scenes with Synergy in the book (yes, still in progress.)

Cyberpunk (1990) documentary cover.

ND: There are a lot of different reasons posed for Mondo 2000’s eventual halt in publication. Is there any one reason that you think was the root cause?

RU: Insanity.

ND: In Synthetic Pleasures (1995) you said that “the way to eroticize the brain is to explore sexuality with new media.” With the popularity of the Oculus Rift and virtual reality in general right now, how do you think the ideas of sex and eroticism will mingle with these technologies going forward?

RU: Did I say that? :-) Many knew mediums gain their financial foothold via porn. What will virtualized eroticism bring to the party, not just in terms of porn but in terms of real sexual connection? It seems to me that a lot of relationships take place mainly online now. Gender, genital sex, smells… are these things becoming obsolete? I don’t know. I can’t get no satisfaction from any sort-of totalist approach, myself…

ND: What’s the current status of the Mondo 2000 History Project?

RU: Negotiating a book deal. Otherwise, close… Not knowing the format has complicated its completion.

ND: I noticed recently that Mondo 2000 has a new twitter account and an announcement of a website coming soon. What are your future plans for Mondo 2000? Can we expect a Mondo 3000 to come soon?

RU: Mondo2000.com … it should be operational by the time people are reading this…

ND: While I’m of the belief that Mondo 2000 was something truly unique, is there any organization or publication these days that carries the same spirit?

RU: Dangerous Minds covers some of the territory. Boing Boing covers some of it. Coilhouse was awesome but has apparently disappeared. I don’t think anyone would do Mondo 2000 now in the way we did it. It was – dare I say – radical but politically incorrect in a way that is much more difficult to approach in a playful manner now. I’m still not sure how I’m going to navigate that aspect of our change in the culture with mondo2000.com.

Mondo 2000 hypercard via Boing Boing.

ND: I’ve noticed in the past that you keep an eye out for articles online that mention Mondo 2000. Are there any websites or other publications that you read regularly?

RU: My morning online commute runs as follows… recent facebook posts, recent Google+ posts, Boing Boing, Vice, RAW Story, Reason, Huffington Post, io9, The Intercept, Washington Post, Dangerous Minds, ego search for R.U. Sirius, Mondo 2000, Timothy Leary, Ken Goffman. My Steal This Singularity twitter. (Now) Mondo 2000’s twitter.

ND: Are there any big things you are working on these days that should be on our radar?

RU: I like doing lyrics and music more than anything else. I have lyrical song cycles – some that have actual songs and some that have just lyrics — that I like as much as anything I’ve ever done. I’ll probably post them on Mondo2000.com. I think some of the new stuff that I will be working on with R.U. Sirius & Phriendz and some other folks will be stunning… It’s hard to get people to check it when they don’t know you for music though. People are real twats about that. (My bandcamp…)

ND: Do you currently have any plans for more music coming up?

RU: Working on a bunch of songs… some may have my voice others not. R.U. Sirius & Phriendz may see the most production. Another artist who is known in the jazz world but who will be working under a pseud is working with me on some stuff. We’ll see.

I posted this sort of lyrical conceptual thing just recently. I’d love to get that done as a thing. Some of the songs exist already…

ND: Many theoretical topics or downright crazy ideas from Mondo 2000 are becoming reality. How do you view the future these days? Where do you believe we are headed?

RU: The blurring of reality – the disbelief in even functional truth - has entered too deeply into the realm of the political… People grasp for certainties, ideologies, authority… even anarchist authority if that’s their leaning. More chaos. Existential threats like the weather; increases in nationalism and racism and hostility; the spread of nukes… There’s this sort of quasi-Leninist notion that bad material conditions lead to revolutionary progress. Not true. They lead towards authoritarianism and reaction.