Recollecting The Future— An Omni Retrospective

This article was originally written for and published at Neon Dystopia on June 28th, 2017. It has been posted here for safe keeping.

The first time I read anything out of Omni, I probably had a completely different experience than you did. The original run of Omni, the iconic science and science fiction magazine, ran in print from 1978 to 1995, ending when I was just four years old. The first time I eyed the pages was maybe only five years ago — on my computer screen, with issues batch-downloaded from the Internet Archive back when you could find them there. While I didn’t get that feeling that comes with curling, sticky-with-ink pages between my fingers, or the experience of artificial light reflecting off of the glossy artwork and into my retinas, I was able to ingest the rich content all the same. While there is something sterile and antiseptic about reading magazine scans from a computer, there is more to say about reading Omni, in particular, this way; what the readers have been dreaming about since the publication’s inception has become reality. I have a whole archive of Omni issues that I can take with me everywhere in my pocket. To reference an oft-used quote from Ben Bova, previous editor of Omni, “Omni is not a science magazine. It is a magazine about the future.” The future is now, and maybe some things did end up changing for the better.

The iconic Omni logo.

Omni (commonly stylized as* OMNI*) got its start in a rather interesting way back in the late 1970s. Publisher Kathy Keeton, who had previously founded Viva (1973), an adult magazine aimed at women, and held a high-ranking position at the parent company for Penthouse (1965), proposed an idea for a new type of scientific magazine to Penthouse founder and her future husband, Bob Guccione. Keeton and Guccione would develop the concept of a magazine focusing on science, science fiction, fantasy, parapsychology, and the paranormal. It was a departure from both the over-the-top, pulp science fiction magazines of the 1940s and stiff academic scientific journals of the time aimed at pipe-smoking professionals in three-piece suits. Omni was aimed more at the layperson in that its content was accessible yet serious — they bought into their own brand and expected you to as well.

Guccione and Keeton, image via dailymail.co.uk.

A strange departure from the pornographic roots of both Keeton and Guccione, Omni was a completely new beast, eccentric and untried. While other science publications looked to ground their content in what was concrete, Omnifocused on the future with wonder and a sense of possibility. An issue may contain irreverent, gonzo articles about alien abductions, chemical synthesis of food, what personality traits should be given to robots, thoughts on becoming a cyborg, or the computer-centric musings of lunatic/genius Ted Nelson. You could find articles on drugs back-to-back with discussions of high-tech surgical procedures or homebrew aeronautics. No topic was off limits, and with decent rates for writers, the weird had a chance to turn pro. Whether it was intentional or not, Omni adopted a laid-back, transgressive west coast culture that praised the strange and favored the “out there.” For a lot of readers in the late 1970’s, this was the only place to get this type of content. People couldn’t pull out a cell phone and hop online to get the vast swathes of information that we can now – there was an ever-present undertone of information isolation, and Omni filled the void.

Omni‘s premier issue, October 1978.

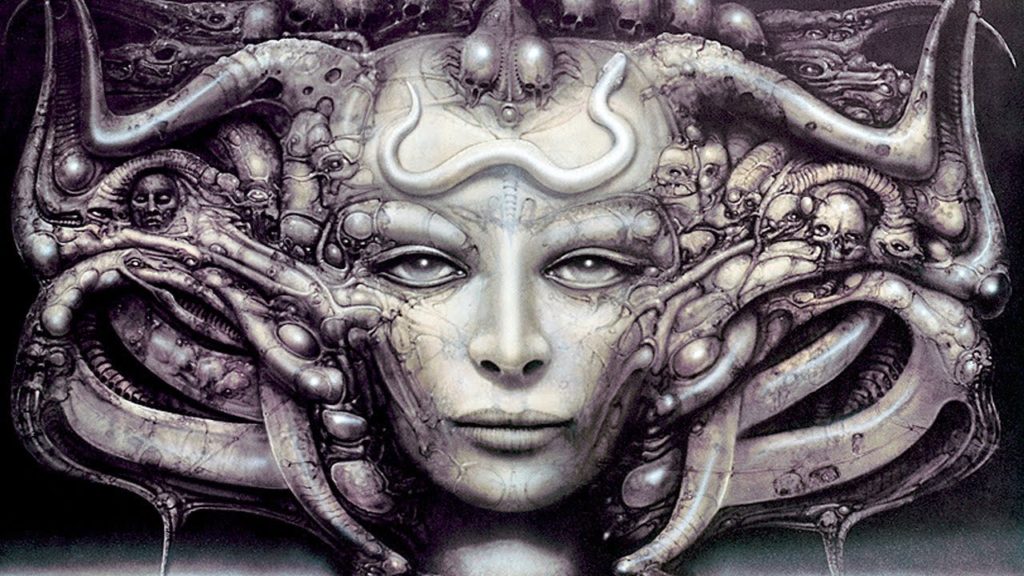

While the magazine was well known for its articles and comprehensive interviews with the scientific elite such as Future Shock (1970) author Alvin Toffler or astrophysicist Carl Sagan, the most flirtatious quality of Omni was its illustrations. Slick and glossy, Omni never failed to draw a shy eye from a newsstand with bright colors and airbrushed art of feminine androids or lush mindscapes in high contrast. Many notable artists contributed their work to Omni, including John Berkey, H.R. Giger, and De Es Schwertberger. For each issue, the gold-chain-wearing Guccione would be said to personally pick the featured art; each image was part of what he wanted to convey with the magazine, and it might be more than a coincidence that many of the covers featured women. Omni wasn’t the only publication of the time with intricate cover art, as Heavy Metal (1977) featured similarly detailed depictions, and even shared some of the same artists. Where Omni really set itself apart from others was through the use of artwork throughout the periodical as a whole. With sprawling, multi-page illustrations, the art didn’t take a backseat to the articles. Just flipping through, someone might think that they had picked up an art magazine; Omni was never one to skimp on the visuals.

H.R. Giger’s Dune concept art would grace the cover of Omni‘s November 1978 issue.

Above all of the articles and artwork, Omni may have been most celebrated for its short fiction. At its inception, nobody really knew how to react to Omni’s foray into the science fiction ecosphere. The SF community was tight-knit and amiable, but it wasn’t exactly used to sleek publications from groups that had no background in the subject showing up suddenly in bookstores and comic shops. Keeton and Guccione did their homework and hired notable editors, Ellen Datlow and Ben Bova (a six-time Hugo Award winner during tenure as editor of Analog Magazine (1930)), to seek out content for publishing. Like Bova, Datlow was a fan of the genre herself and wasn’t afraid to push the envelope when it came to buying far-out fiction. The magazine came to showcase science fiction for science fiction fans, and didn’t subdue or water down the content for the sake of a broader audience – the bottom line was never sacrificed. With contributors like Robert Heinlein, Orson Scott Card, Isaac Asimov, William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, George R.R. Martin, and William S. Burroughs, there were not only excerpts from larger works but complete short stories introduced to the world for the first time. William Gibson notably published “Burning Chrome” (1982), “New Rose Hotel” (1984), and “Johnny Mnemonic” (1981) through Omni, creating the foundation for the Sprawl that would later host some of his most celebrated novels: *Neuromancer *(1984), Count Zero (1986), and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988). Omni helped launch the careers of many science fiction authors, and fostered exposure for countless others over its near three-decade reign.

The first page of William Gibson’s “Burning Chrome,” featured in Omni‘s July 1982 issue.

Omni thrived for many years as it continued to dazzle readers with exciting and thought-provoking composition. Eventually, Omni would get its own short-lived television show, Omni: The New Frontier (1981), a webzine on Compuserve, and six international editions with varied amounts of both reprinted and original articles. Later in the publication’s life, the articles took a more paranormal slant that left many fans and contributors wondering about the magazine’s direction. Keeton and Guccione had always held a lot of interest in the paranormal and found a kindred spirit in their editor-in-chief, Keith Ferrell, who took up the position in Omni’s twilight years. While Ferrell wanted to shift Omni’s focus towards the vetting of the unexplained, the magazine couldn’t sustain itself for much longer. Omni published its last print issue in the Winter of 1995, citing rising production costs. At the time, Omni had a circulation of 700,000 subscribers, many of whom were left high and dry if they hadn’t already abandoned the publication with the recent shift in focus. While it is unknown whether or not production costs were to blame for Omni’s demise, many surmise Guccione’s strategy of funding Omni via Penthouse’s profits was starting to fall apart. While free Internet pornography flourished in the 1990’s, it put the older print industry in jeopardy. The ship was sinking, and something would need to be thrown overboard before the situation would get any better for the Penthouse empire.

“Some of Us May Never Die,” article by Kathleen Stein, October 1978.

Omni did not disappear completely, and successfully transitioned into an online-only magazine dubbed Omni Internet in 1996. At the time, there were few examples of magazines who could make the jump to digital. Omni embraced the new format which allowed them to play with how content was structured and draw in fans with interactive chat sessions. While a conventional magazine could only be published once a month, Omni could now report on scientific news as it happened, setting a standard in web-based journalism that we still see today. This was a “blog” before Jon Barger coined the term the following year, and it holds a spot as an early example of the format. In 1997, Kathy Keeton died due to complications from surgery and Omni closed down completely just six months later. While Omni was the brainchild of both Keeton and Guccione, Keeton had always been the main driving force that held all of the moving parts together. The publication that always promised to bring the future would now become static, slowly fading into the past with each passing year. While no new content was published, the site remained online until 2003, when Guccione’s publishers filed for bankruptcy.

AOL welcomes you to Omni Online, one of Omni‘s first forays into the web. Image via http://14forums.blogspot.com

While Omni may have ceased production, its strong legacy cannot be questioned. While fans wax rhapsodic about the old days, there are plenty of remnants left over that have diffused the iconic Omni spirit to new generations. Wired (1993) owes just as much to Omni as it does its precursor, Language Technology (1986), as well as Mondo 2000 (1989), bOING bOING (1988), and Whole Earth Review (1985). While Wired didn’t rely on science fiction, it still yearned for a techno-utopian future and even hired on some Omni expatriate short fiction writers to become reporters for the new digital revolution. Later in 2005, a much-unknown omnimagazine.com was launched, claiming to be cared for by former staff and contributors of Omni, including Ellen Datlow, the fiction editor who worked at Omni for nearly its entire run. In 2008, the website io9 was created by Gawker Media (Later a property of Gizmodo) specifically to cover science and science fiction, just as Omni had done decades before. io9’s slogan, “We come from the future,” echoes Ben Bova’s Omni quote, and helps cultivate an image of the site as a spiritual successor.

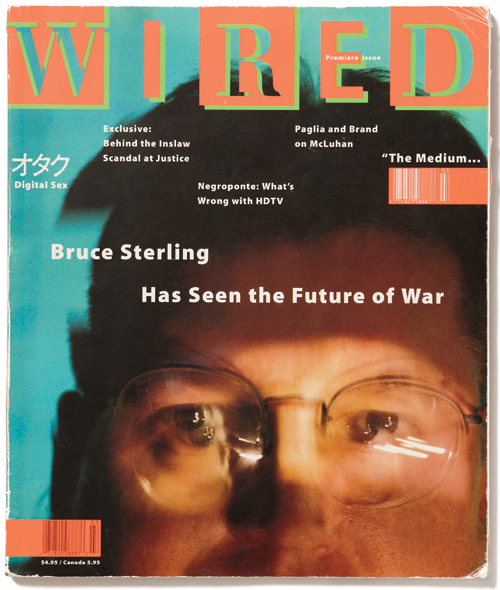

Wired issue #1 from March, 1993. The cover features an article by science fiction writer and Omni contributor Bruce Sterling.

In 2010, Bob Guccione passed away at the age of 79 following a battle with lung cancer. While Guccione’s death didn’t immediately influence the future of Omni, it set off an interesting chain of events that would ultimately lead to a rebirth of the publication. In 2012, businessman Jeremy Frommer bought a series of storage lockers in Arizona, one of which happened to contain a large amount of Guccione’s estate. Frommer was enamored by his discovery and immediately fell down the strange and multifaceted rabbit hole of Guccione’s mind. With the help of his childhood friend, producer Rick Schwartz, Frommer started building The Guccione Archive in a nondescript New Jersey building. Out of the entirety of Guccione’s life work, Frommer became fixated on Omni and explored the collection of production materials, pictures, 35-mm slides, and original notes generated from the life of the magazine. It wasn’t long before he brought in others to sort the collection and track down original artwork used for Omni that he could purchase and add to the archive. For Frommer, it became a passion to create the most complete collection of Omni-related materials, and he had to get his hands on every bit he could find.

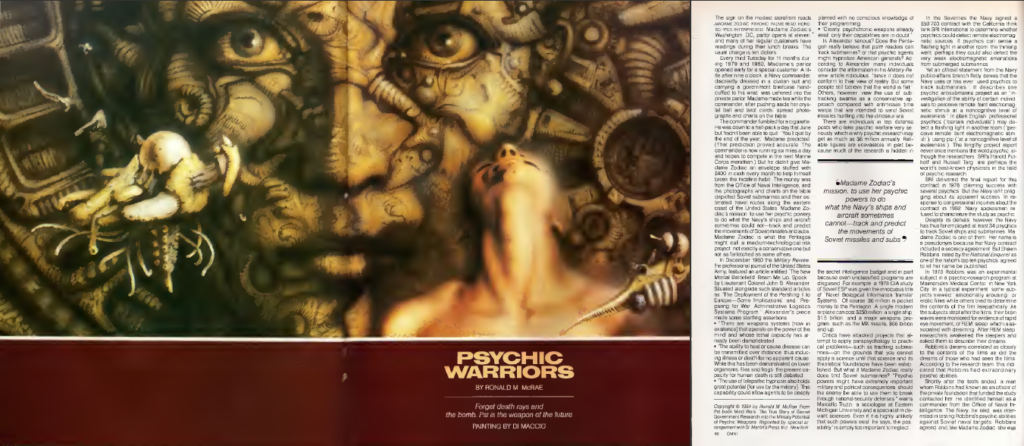

Artwork like this Di Maccio piece showcasing “Psychic Warriors,” by Ronald M. McRae was being tracked down to add to the archive.

Organically, Frommer came to the conclusion that he needed to take the next logical step: he needed to reboot the magazine. When Claire Evans, pop singer and editor of Vice Media’s Motherboard blog, met with Frommer to cover the Omni collection, she was asked if she would be interested in working on a new Omni incarnation. In August 2013, Evans was named editor-in-chief of Omni Reboot and got to work. The new publication was off to a strong start as Evans was able to get submissions and interviews from former Omni alumni and science fiction icons like Ben Bova, Rudy Rucker, and Bruce Sterling. Free scans of Omni back issues were made available at the Internet Archive, and the blood once again flowed through Omni’s withered veins. Nostalgia was in full force as people rediscovered their favorite article or got caught up in the whole journey of the reboot. Quickly though, criticism came in about the quality of the content and what would become of the Omni legacy under the new owners. Not everyone thought the magazine should be rebooted.

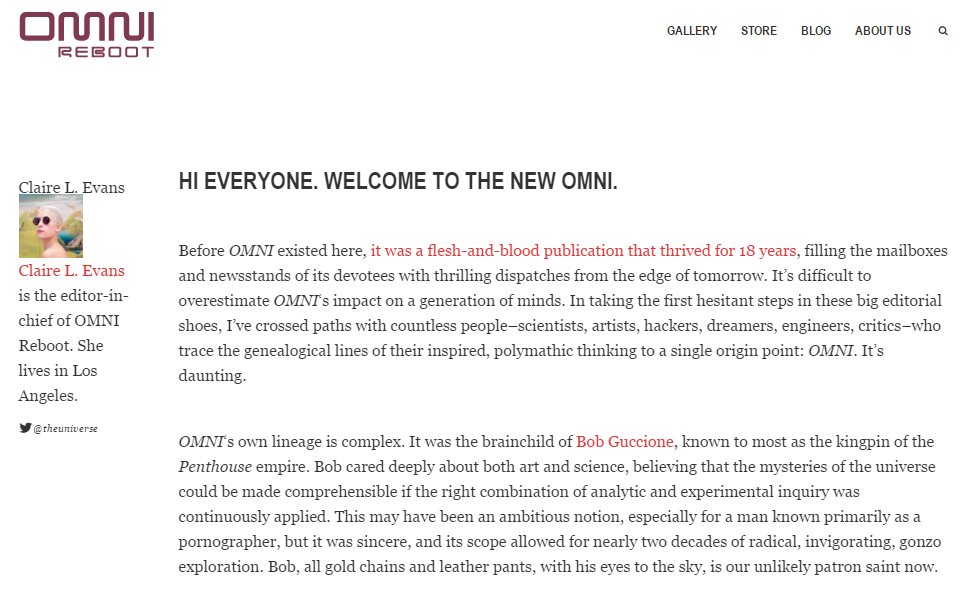

An Excerpt from “Hi Everyone. Welcome to the New Omni,” by Claire Evans served as the introductory article to Omni Reboot (August 2013).

While Omni Reboot still conformed to the science and science fiction roots of the original, it did so with a higher dose of cynicism than even the original obtained. When the old fantasies of science and technology started to become reality, it was only natural for people to consider how the world around them could grow to bite its master and send civilization into a negative spiral. In many cases, it already had. In contrast, the zeitgeist 40 years ago slanted more towards the hopeful idyllic; people used to have conversations about how an advancement would influence mankind and drive the world ahead. That’s not to say everything back then was so hunky dory – we always see the past through rose-colored colored glasses, smoothing over the corruptions and jagged edges in our memories. While the world aged and evolved, so did opinions towards its technocentric trajectory. Etherealism was no longer en vogue.

As the reboot grew it started to come under fire from authors as it was discovered that submitted work would become owned by Jerrick Media, *Omni Reboot’*s new parent, for a year after publication. Further fueling controversy, the back issues of Omni on the Internet Archive were removed in 2015, much to the disappointment of readers. In 2016, Jerrick Media released Vocal, a publishing platform for freelance writers to make money based on article views. Omni Reboot(now just Omni) was re-purposed as one of Vocal’s verticals, serving as an interface for science and science fiction related submissions from the Vocal content network. Browsing Omni now, there is an overwhelming, uneasy feeling of quantity over quality. A name that once stood proudly and represented a home for the weird and futuristic had become just a limb on a larger, alien body.

Omni’s current homepage, via omni.media.

A few weeks ago in May of 2017, we got another chance to relive the rich history of Omni as back issues became available once again. Unlike the older Internet Archive scans, these new transfers are in high resolution, with each and every issue accounted for. Also unlike the older transfers, each issue costs $2.99 for a digital copy, though they are free if you happen to be a Kindle Unlimited subscriber. While it’s bittersweet that these issues are now available for pay, profits from their sales are going to a good cause. Omni announced a partnership with the Museum of Science Fiction who receive a portion of the revenue from each purchase.

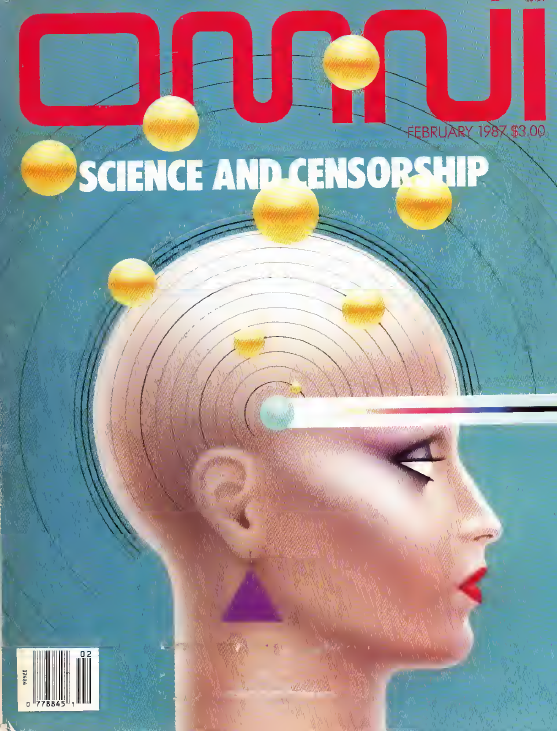

Cover of Omni‘s February 1987 issue. Just one of many back issues that are now available for purchase.

While Omni has changed many times over the years, it is still remembered as that wondrous and weird, crazy and cool publication delivered to mailboxes month after month. Omni worked best because it didn’t try to fit into an existing space, it pioneered its own; It became a destination that amalgamated the new, the scary, and the unknown. In the true Omnispirit, we have no idea what is coming for the publication as the clock ticks ahead. Will it thrive and continue on, or become another ghost in the machine, slowly obsolescing.

The future is ahead of us, and for now, we can only look to it with hope and wonder.

We can only look to it just like Omni would want us to.