‘More Than Just A Game’– Brainscan Review

This article was originally written for and published at Neon Dystopia on May 22nd, 2017. It has been posted here for safe keeping.

In the mid-1990’s, we saw cinema saturated with cyberpunk movies. Some became staples of the genre, while others simply faded into obscurity. Brainscan (1995) combines elements of cyberpunk and horror, to create a unique story about a video game gone wrong. While not a particularly successful film, Brainscan turns out to be an interesting extension to the classic “killer computer” trope. At a time when owning a computer has become normal for your average household, it’s easy to ponder how things could go wrong, especially in the style of a Twilight Zone fever dream.

Upon watching, Brainscan instantly makes you feel uneasy with its instrumental score, and it is something you will notice over the course of the entire film. The electronic music quickly fills any scene with dread, reminiscent of 1978’s “Halloween Theme Main Title” (from the film of the same name) by John Carpenter. Coupled with a dark color palette, the mood is set and unchanging. While the film definitely exhibits a horror-themed, fanciful atmosphere, make no mistake about its ties to the cyberpunk aesthetic. Technology, and our inherent fear in embracing it (as a species), sits center stage for the full run of the story. Likely influenced by publications of the time such as Mondo 2000, we get a taste of the cyberdelic lunatic fringe.

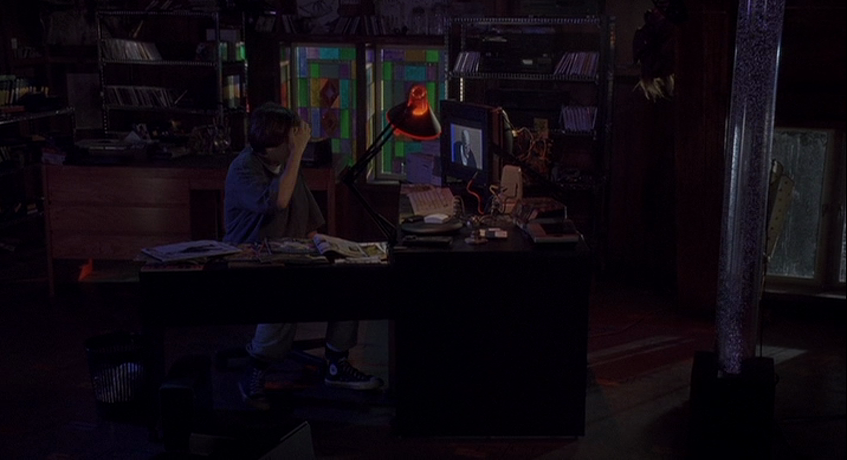

When our protagonist Michael (Edward Furlong) is told about a horror-filled video game that interfaces with a player’s subconscious, he’s eager to call up the phone number printed in a Fangoria advertisement to place an order. His appetite for blood and gore is insatiable, but the game isn’t what he bargained for. Furlong gives an excellent performance, tapping into some of the same themes exhibited by his Terminator 2 character, John Connor, a few years earlier. Michael himself easily fills the role of the smart high school student. He has a voice-controlled computer, Igor, which he primarily uses to place and take phone calls. Red-light-drenched computer hardware spans a large section of his attic bedroom, including an interface to his video camera which he uses to spy on the neighbor-cum-love-interest, Kimberly (Amy Hargreaves). You may call him an introvert, or a misfit — he has few friends and even less family but seems close to his best friend, Kyle (Jamie Marsh).

The bedroom of my teenage dreams.

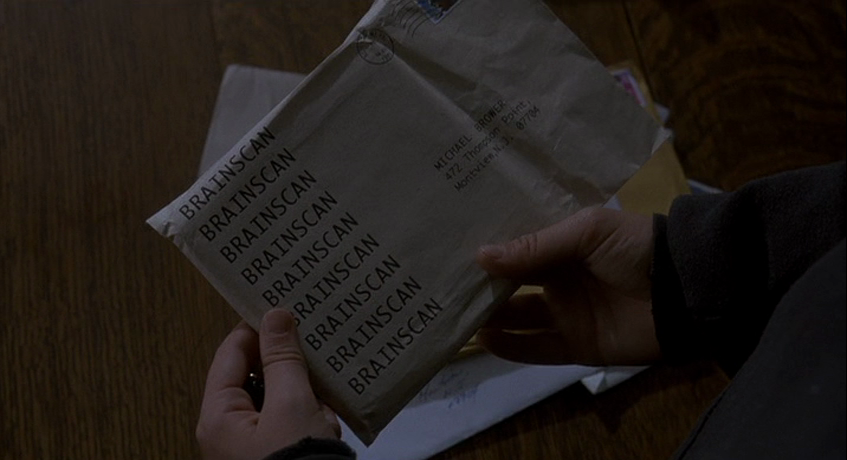

Upon calling Brainscan, Michael is told about the innovative, fully-customized game and gets electrically shocked before the mysterious voice on the other end of the line tells him that his game has been decided and the first disc will be mailed to him. At this point, I liken Michael to transgressive characters of other films, such as Thomas Anderson / Neo of The Matrix (1999) or David Lightman of WarGames{.} (1984), who transcend connotations of the 1950’s idyllic and its three-piece psychology. In fact, I’d stress that there are a lot of parallels between this film and WarGames — the technophile wiz-kid finds a mysterious phone number which ultimately wreaks havoc on his life. When the first Brainscan disc shows up in the mail, things take a dark turn when Michael boots it up and is instantly transported into the game, seemingly immersed by the “subconscious interface” which creates something akin to an out-of-body experience. In a first-person view, Michael is instructed by a methodical, disembodied voice to commit a murder, which he dutifully complies with. When Michael sees the news the following day, he quickly realizes that the murder was real. The virtual reality has leaked over into the natural world, and the line between them starts to become fuzzy.

The first disc arrives.

At this point, Michael gets a visit from the Trickster (T. Ryder Smith), who materializes out of thin air in his bedroom. Trickster, resembling an undead hard rock front-man, seems to know everything about Brainscan and urges Michael to keep playing until he completes the entire game. If Michael has been a middling character up until now, toeing the line between a rebel and a complaisant, we see him reevaluate his morality as the Trickster begins to impose more and more chaos in Michael’s life. Michael isn’t only pitted against Trickster, but the game itself which Trickster seems to be connected to. He’s lashing out against the technology that has betrayed him but is helpless in combating it.

The Trickster will threaten you with a CD.

*Spoilers Ahead*

Michael is worried about getting caught and reluctantly agrees to keep playing Brainscan in order to tie up any loose ends that may implicate him in his crime. Feeling like he has no other options, Michael continues to kill before standing up to Trickster and refusing to commit a final act. Disappointed by Michael’s act of defiance, Trickster allows the police to shoot and kill Michael. Michael has finally broken out from the game and immediately wakes up in his chair just as he did after playing for the first time. The whole experience was just part of the game, and none of it actually took place. Realizing this, Michael completely destroys all of his computer equipment, symbolically freeing himself of his technological imperative and escapist tendencies.

Complete destruction.

While Brainscan doesn’t incorporate many cyberpunk visuals, it certainly captures the essence of cyberpunk itself. Much like Black Mirror’s “Playtest” episode, we see a main character who seems to detach from reality and chooses to escape into technology to chase a high that he cannot derive from the physical world. While Michael may not fit seamlessly into a generation of young adults who have complete access to information and media, he exhibits traits that make him susceptible to escapist behavior and the dangers that go with it. Exploring his infatuation with high-tech entertainment, we become aware of what can happen when fantasies overlap with reality. Can we expect similar real-world stories to come forward as virtual reality worlds become more immersive and realistic? Maybe we don’t even have to go that far. Is it a stretch to consider that players of conventional video games have difficulty disassociating with them after putting down the controller? Little stops these experiences from bleeding over into our day-to-day lives, especially for the self-actualizing who may be hesitant or unable to make the distinction.

Are you ready to play?

While the premise of Brainscan certainly fits within the cyberpunk genre, the film is not without its shortcomings. Furlong and Smith give notable performances, though the supporting characters are more one-dimensional. At 22 years old, the physical technology we see is laughably dated at times, despite the topical concerns brought up by the story. Brainscan would never win any awards, but it’s a fun guilty pleasure that you want to keep watching. Just make sure you don’t order any video games out of a magazine anytime soon.