Philosophy of Data Organization

I would be a liar if I said I was an overly organized person. I believe that like things should be grouped together and everything is to have its place, but I follow something of a level of acceptable chaos. Nothing is organized completely, and I don’t really believe it is possible to have complete organization on a large enough scale. Complete organization is likely to cause insanity.

When I first started accumulating data, I quickly outgrew my laptop’s 80 gigabyte hard drive. From there I went to a 150GB drive, then a pair of 320GB drives, then a pair of 1TB drives, then a pair of 2TB drives, and from there I keep amassing even more 2TB drives. As I get new drives, I like to rotate the data off of the older ones and on to the newer ones. These old drives become work horses for torrents and rendering off video while new drives are used for duplicating and storing data that I really want to keep around for a long long time. The system is ad-hoc without any calculated sense of foresight. If I had the money and planning, I’d build a giant NAS for my needs. For now, whenever I need more space, I just buy another pair of drives and fill them up before repeating the cycle. This doesn’t scale very well and I ultimately around 25TB of storage scattered across various drives.

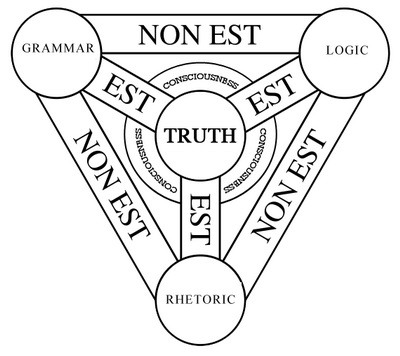

A few months ago, I was fortunate enough to take a class on the philosophy of mind and knowledge organization. A mouthful of a topic, I know, but it is more simple than it seems. The class revolved around one main concept: classification. We started with concepts put forth by Greek philosophers on how to organize knowledge via the study of knowledge: epistemology. We start out with concepts put forth by Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. Notably, university subjects were broken into the trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) and later expanded with the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy) as outlined by Plato. These subjects categorized the liberal arts, based on thinking, as opposed to the practical arts, based on doing. These classifications were standard in educational systems for some time.

A representation of the Trivium.

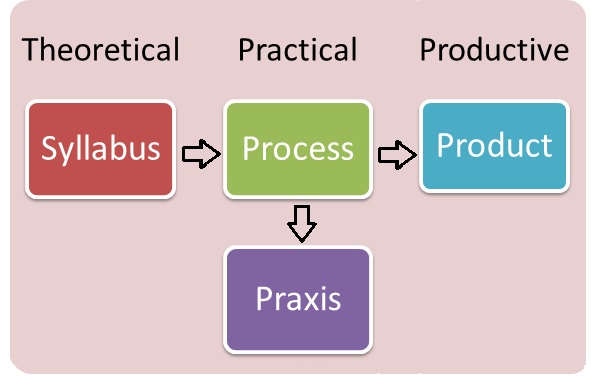

Aristotle reclassifies knowledge later by breaking everything into three categories: theoretical, practical, and productive. This is again broken down further. Aristotle breaks “theoretical” into metaphysics, mathematics, and physics. “Productive” is broken into crafts and fine arts. “Practical” is broken down into ethics, economics, and politics. From here, we have a more modern approach to knowledge organization. We see distinctive lines between subjects which are further branched into more specific subjects. We also see a logical progression from theoretical to practical, and finally to productive to ultimately create a product.

An outline of Aristotle’s classification.

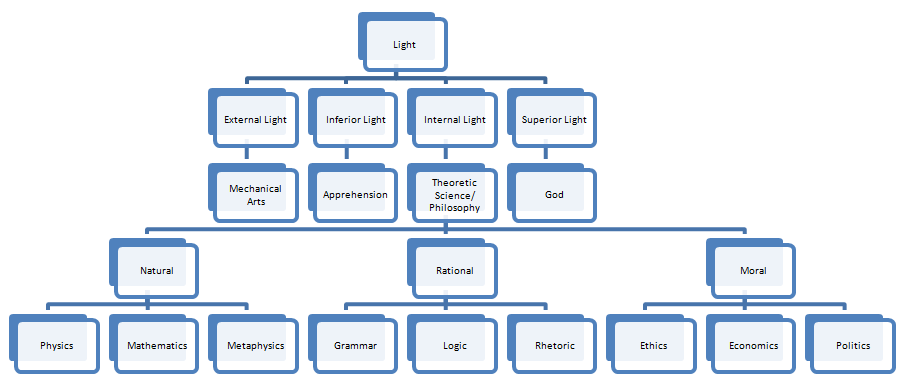

More modern classifications pull directly from these Greek outlines. We can observe works by Hugo St. Victor and St. Bonaventure which mash various aspects of these classifications together to create hybrid classifications which may or may not be more successful in breaking down aspects of the world.

An interpretation of St. Bonaventure’s organization.

What does this have to do with data? Data, much like knowledge, can be organized using the same principles we have observed here. Remember, the key theme here is classification. We are not simply concerned with how to break up knowledge, but anything and everything that can be classified.

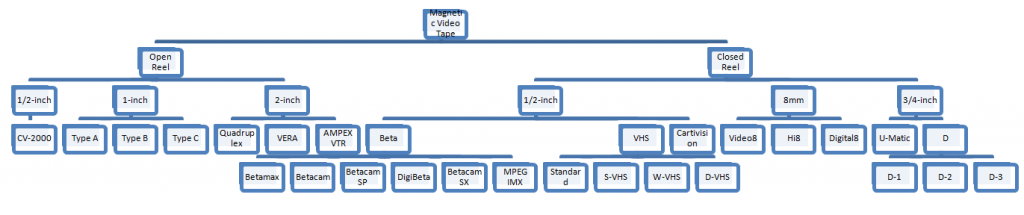

Think of all the possible ways you could organize films or musical artists, or even genres of music. It can be a daunting thing to even imagine. As an overarching project throughout the course, we developed classifications of our own choice. I chose to focus on videotape formats, and quickly created my own classification based on physical properties. I broke down tapes into open/closed reel, tape widths, and format families. While it might not be the best classification, I tried to approach the problem in a way that was open to using empirical truth (conformity through observations) in a way which would allow a newcomer to quickly traverse the classification branches to discover what format he is holding in his hands.

An early version of my videotape classification.

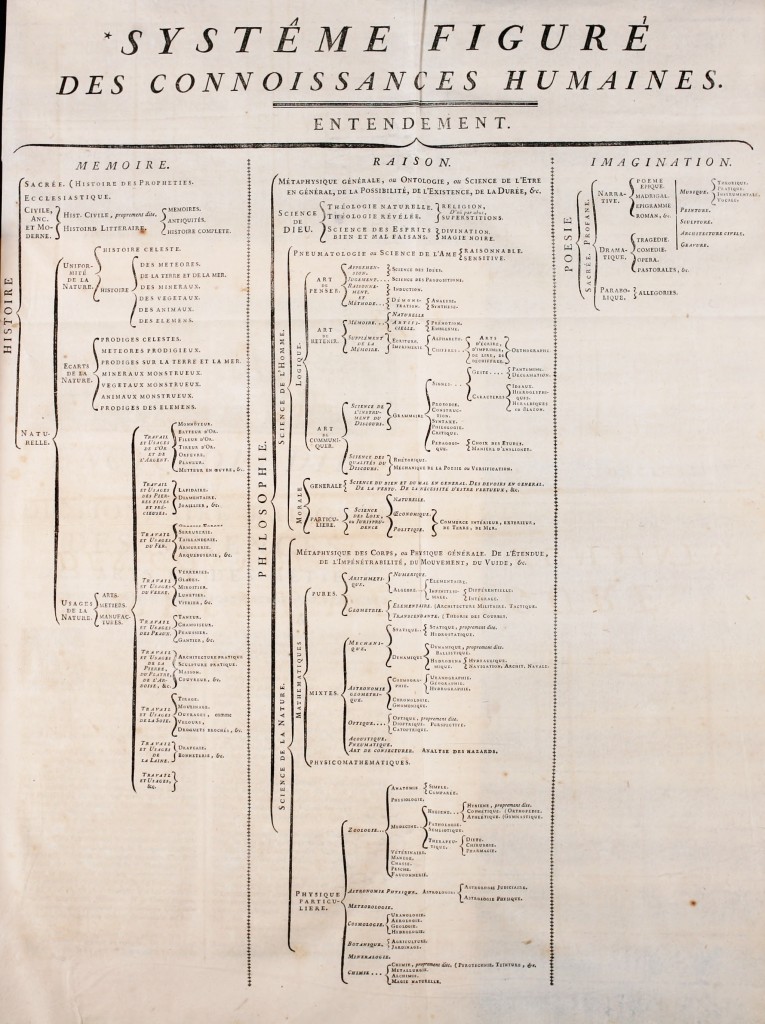

Classifications like this are not uncommon. Apart from the classifications of knowledge put forward here already, classifications have been used by Diderot and d’Alembert to create the first encyclopaedia in 1759. This Encyclopédie uses a custom classification of knowledge as its table of contents. While generalized to an extent (it does fit one page), it could be expanded upson infinitely.

Encyclopédie contents.

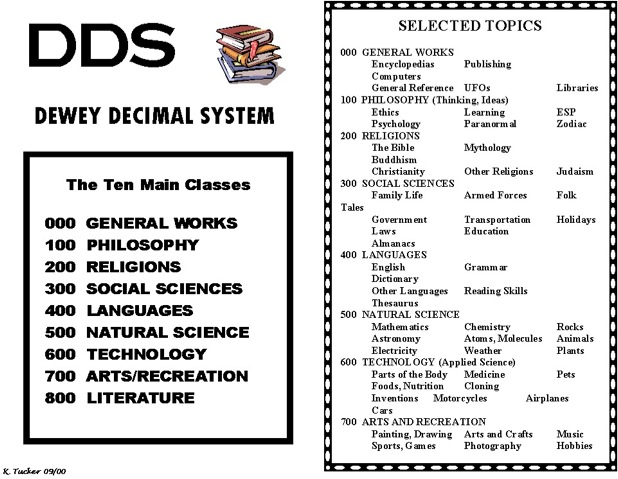

A contemporary way to organize knowledge arrives in a familiar area: the Dewey Decimal System. Though Dewey’s system has been adopted globally as the de facto method for organizing print media, can can we apply this same system to our growing “library” of data? The short answer is no, not without some modification, though modifications have plagued Dewey’s system since its inception.

To understand how we can best organize our data, we must first understand the general concepts of the Dewey Decimal System. Within the system, different categories are defined by different numbers. 100 may be reserved for philosophy and psychology while 300 may be used for social sciences, and 800 for literature. the numbering system here is intentional. Lower numbers are thought to be the most important subjects while higher numbers are less important. These numbers are broken down further. 100 might be broken into 110 for metaphysics, 120 for epistemology, etc. with each of these being broken down again for more finite subjects.

This is just another classification, but it has its faults. The size of a section is finite as the system is broken up into 10 classes which are then again broken down into 10 divisions, and finally 10 sections (hence decimal). However, we never really accounted for the growth of new and expanding topics. As subjects emerge like computer science, which Dewey never could have imagined, we throw works like these into unused spaces. Computer science in particular is infamous as it now occupies location 000, which in the system would make it seem more important than any other subject in the entire system. Additionally, we see a loss in physical ties to the system as libraries are intended to to organized along with the system: lower numbers on the first floor, higher numbers on the higher floors. Dewey’s system is constantly being modified as new works emerge and finding any consistency between different libraries could be controlled by one librarian who chooses whether or not to implement a change at any given time.

A simplified example of Dewey’s system.

While a modified version of Dewey’s system might make sense for data (as well as being somewhat familiar), we have to consider another problem which plagues the classification: titles that can occupy more than one section. Suppose that I have a book about WWII music. Do I put this book in music? Does it go in history? What other sections could it fall into? We have few provisions for this.

Data is no different in this sense. Whether I have a digital copy of a book as would be found in Dewey’s system or a podcast or anything else, there is always the potential for multiple areas a work can fall into. If you visit the “wrong” section where you might expect an object to be, you don’t have any indication that it would be somewhere else just as suitable.

What are we to do in this case? While I like to break my data down into type of media (video, audio, print, etc), I find the lower levels to get more fuzzy. Let us consider a subject which I am revisiting in my own projects: hacker/cyberpunk magazines. Even if we only focus on print magazines, we still have problems. We can see the concept of “hacking” coming from more traditional clever programming origins (such as in Dr. Dobb’s Journal), or evolved from phreaker culture (such as in TEL), or maybe from general yippie counterculture (such as in YIPL). Additionally, we can see that some of these magazines feature a large number of overlapping collaborators which make them feel somewhat similar. We also may observe that magazines produced in places like San Francisco or Austin also have a similar feel but might be much closer to other works that have no physical or personnel ties. Further, what about publications that started as print and then went over to online releases? More and more possible subgroups emerge.

At this point, we might consider work put forth by Wittgenstein which is based off of the “family resemblance theory.” The basic idea behind this theory is that while many members of a family might have features that make them resemble the family, not one feature is shown in all the members who have family resemblance. Expanded, we can say that while we all know what something means, it can’t always be clearly defined and its boundaries cannot always be sharply drawn. Rosch, a psychology professor, took Wittgenstein’s concept further and hypothesized that “the task of categorization systems is to provide maximum information with the least cognitive effort.” She believes that basic-level objects should have “as many properties as possible predictable from knowing any one property.” This means that if something is part of a category, you could easily know much more about it (if you know that 2600 is a hacking magazine, you’ll know there are likely articles in it about computers). However, superordinate categories (like furniture or vehicle) wouldn’t share many attributes with each other. Rosch concluded that most categories do not have clear-cut boundaries and are difficult to classify. This goes on to show the concept that “messiness begins within.” We get a contrast from Aristotelian “orderliness” because messiness shows that we can’t put things in their place because those places are just where things “sort-of” belong. Everything belongs in more than one place, even if it is just a little bit. We see that order can be restrictive.

This raises the importance of metadata: data about data. While my media might be organized in such a classification that doesn’t allow for “double dipping” (going against concepts by Rosch), we can utilize the different properties that pertain to each individual object. Consider many popular torrent sites which utilize crowd-sourced tagging systems. Members can add tags to individual pieces of media (which can then me voted on as a way to weed out improper tags) which allow the media to show up in searches for each tag. We see a similar phenomenon in websites such as Youtube which allow tagging of videos for content, though not in a crowd-sourced sense or the Internet Archive which supports general subject tags as well as more specific metadata fields.

Using this metadata method and my previous example, it’s easy to find magazines by location, authors, subject, contents, age, and a long list of other attributes. We can apply this to objects that aren’t the same format; there are examples of video, audio, and print that pertain to the same subjects, authors, etc. This isn’t an impossible implementation. Considering further the Internet Archive, we see thousands upon thousands of metadata-rich items which are easily searchable and identifiable. However, the Internet Archive also suffers from a lackluster interface. It might be easy to find issues of Byte magazine, but it is a lot more difficult to figure out what issues we are missing or see an organizational flow more akin to a wiki system (though both systems lend themselves well to items being in more than one place). A hybridized system like this would be an option worth exploring, but I haven’t seen an ideal execution of it yet.

While this concept of a metadata-based organizational system isn’t a fool-proof solution, it can certainly be seen as a step in the right direction. We must also consider the credibility of those who decide to make contributions to metadata, especially on a large-scale public system. Consider the chaos and political makeup of how Wikipedia governs editing and then you’ll start to get an idea. While I’d like to implement a tagging system for my own personal media library (with my own tagging at first and the possibility of expansion), I am limited by my current conglomeration of hard drives scattered to different parts of the house, usually powered off. My next storage solution will take these ideas into planning and execution, making my data much easier to traverse. I will however have limitations as I won’t have many people perpetually reviewing and tagging my data with relevant information.

That said, the idea of being able to make my data more accessible is an exciting one, and increases portability of the data as a whole if I ever need to pass it on to others. As my tastes evolve and grow, so will the collection of data I hold.

With any hope, my organized chaos will ultimately become a little more organized and a little less chaotic.

With any luck, you’ll be able to browse it one day.